Monotipias e objetos gráficos

Monotypes and graphic objects

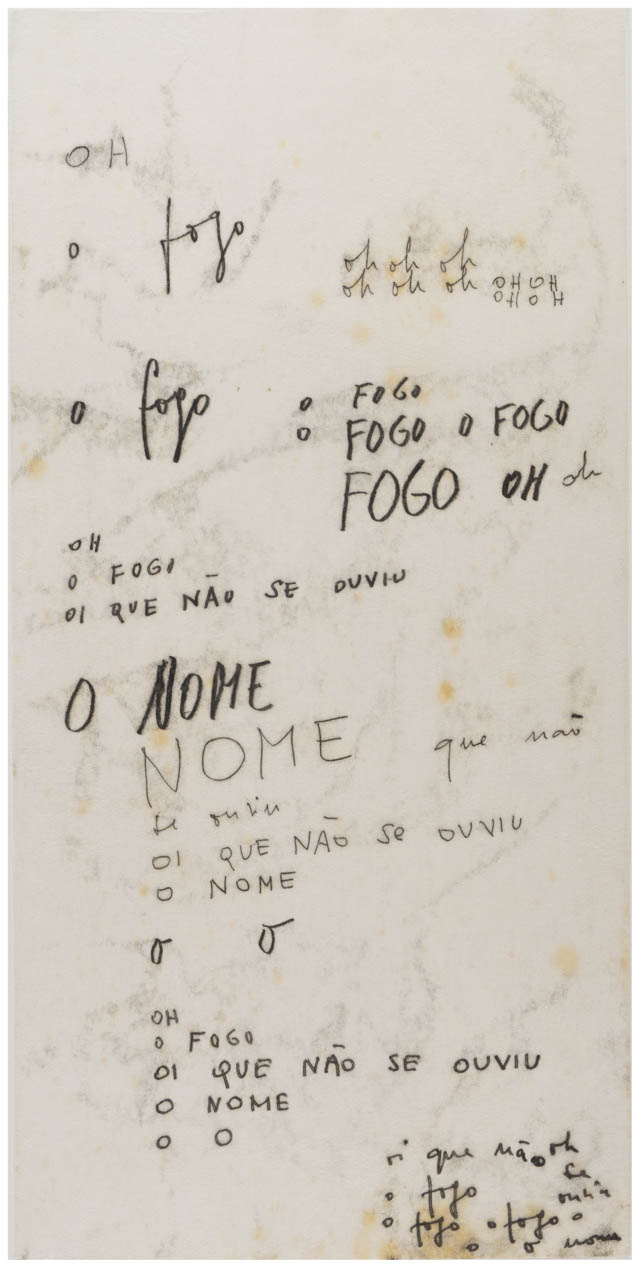

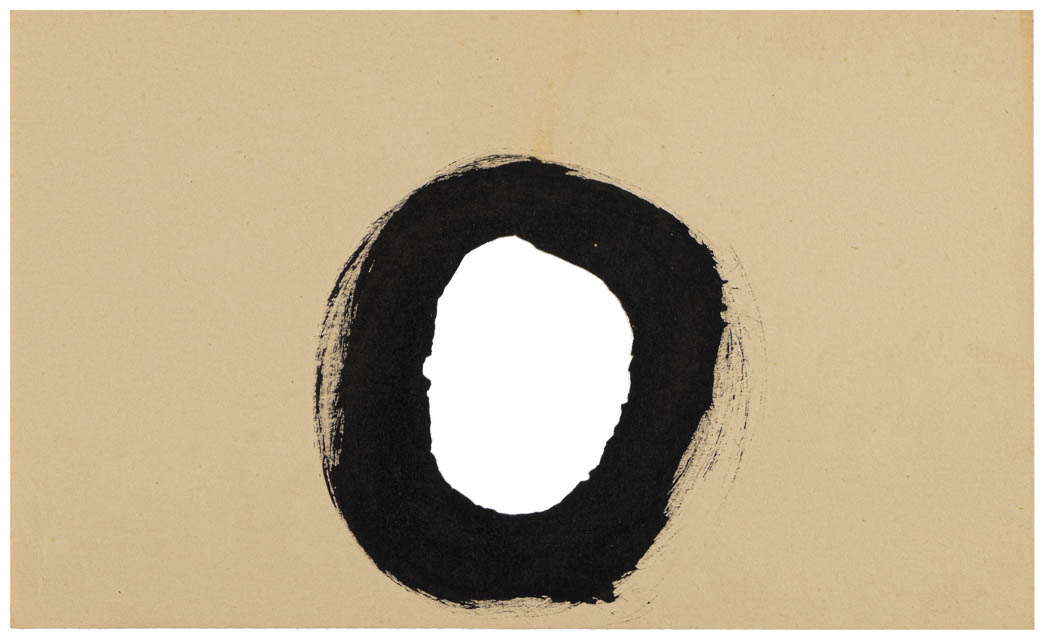

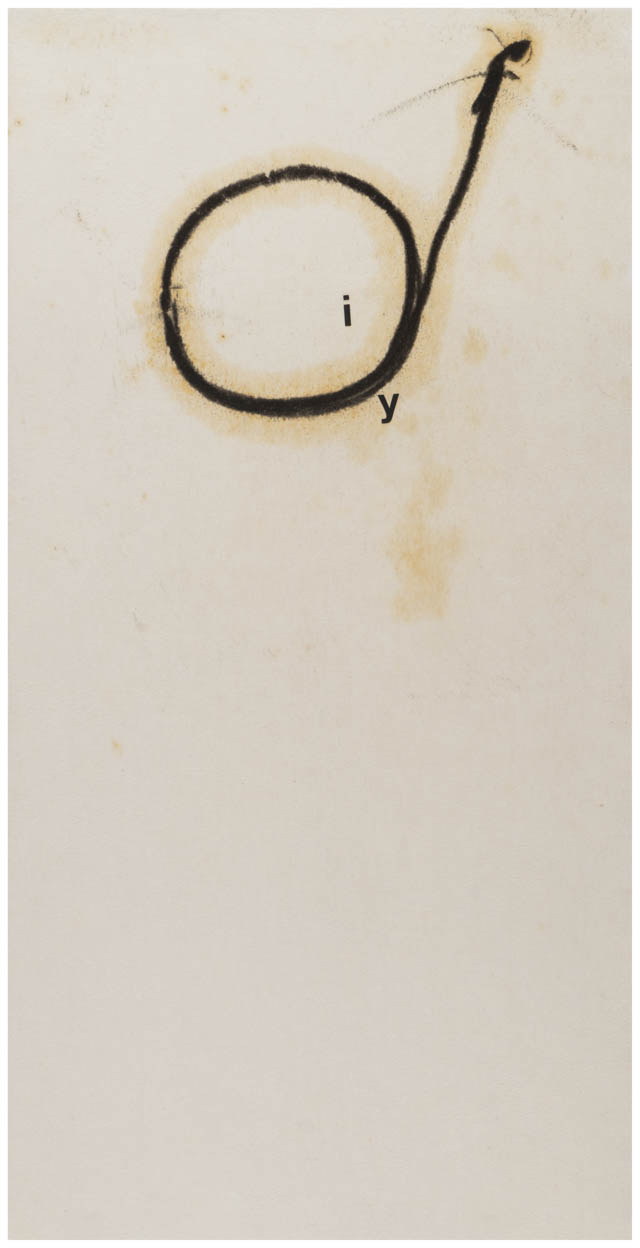

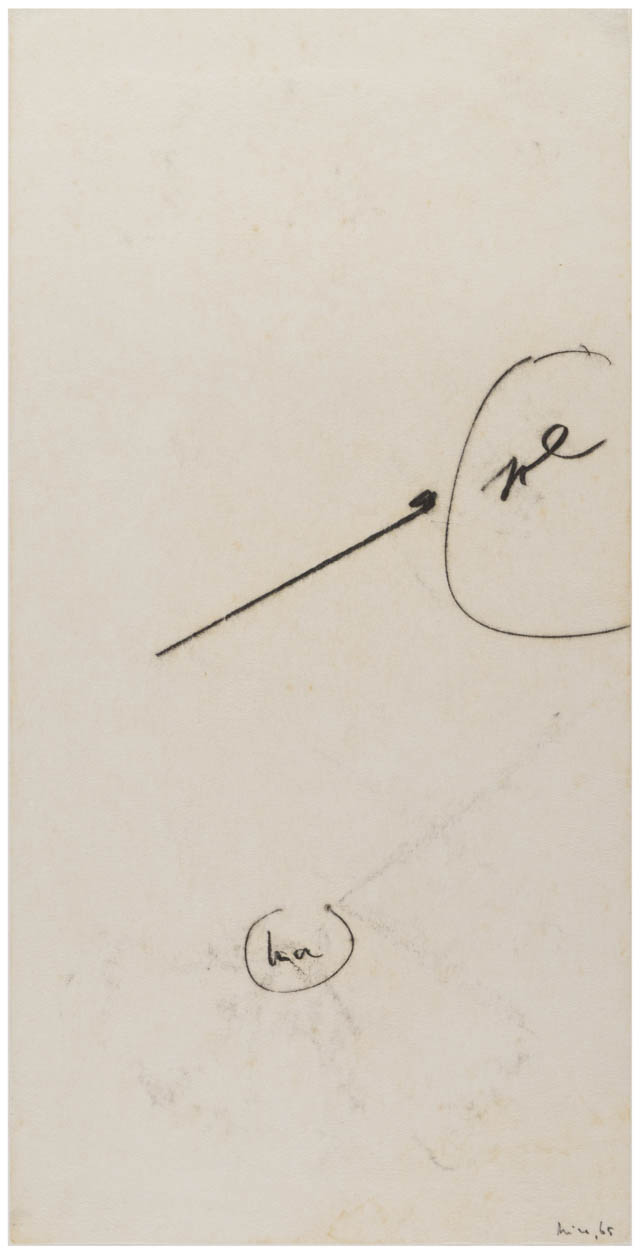

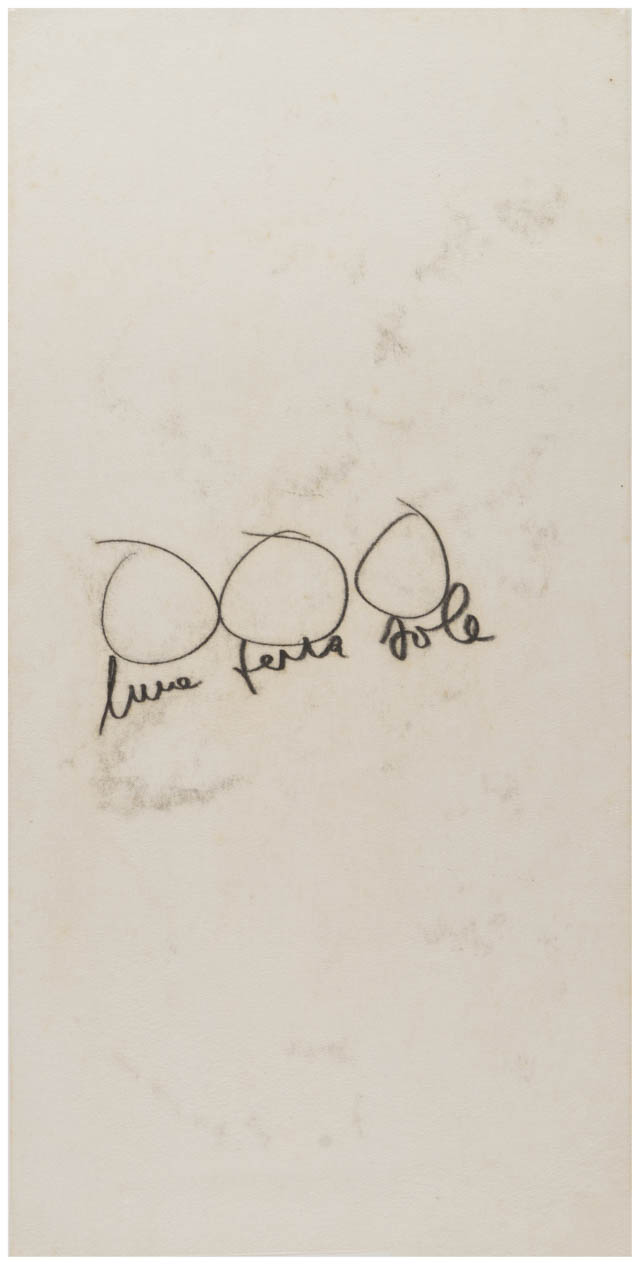

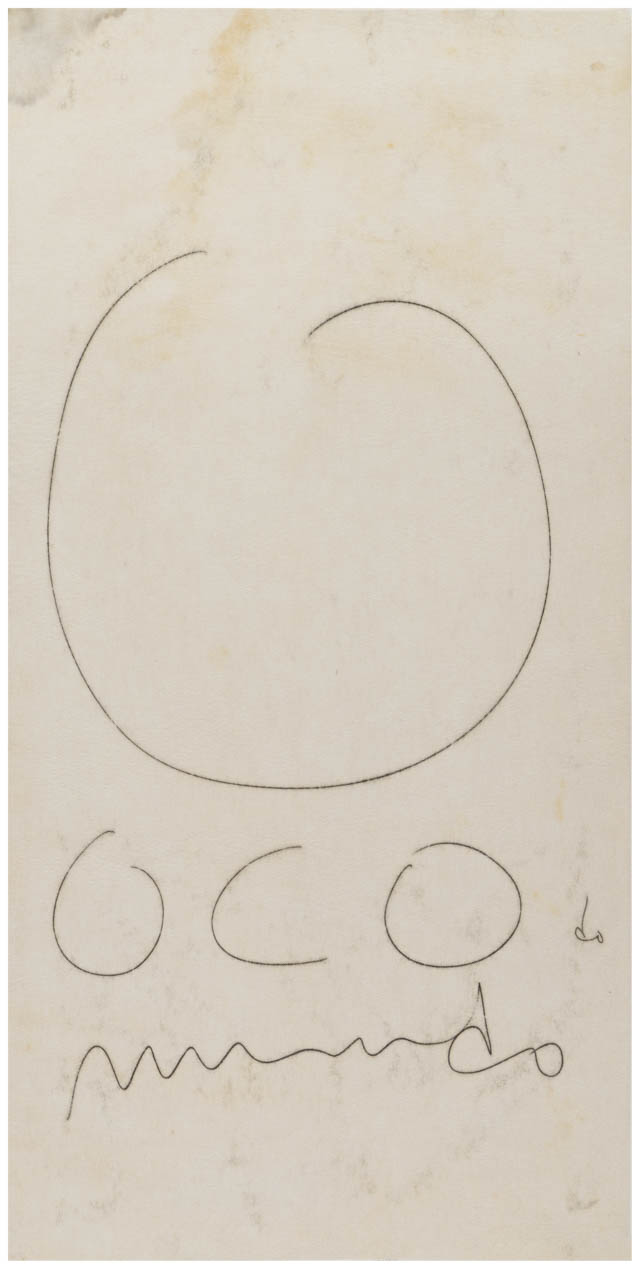

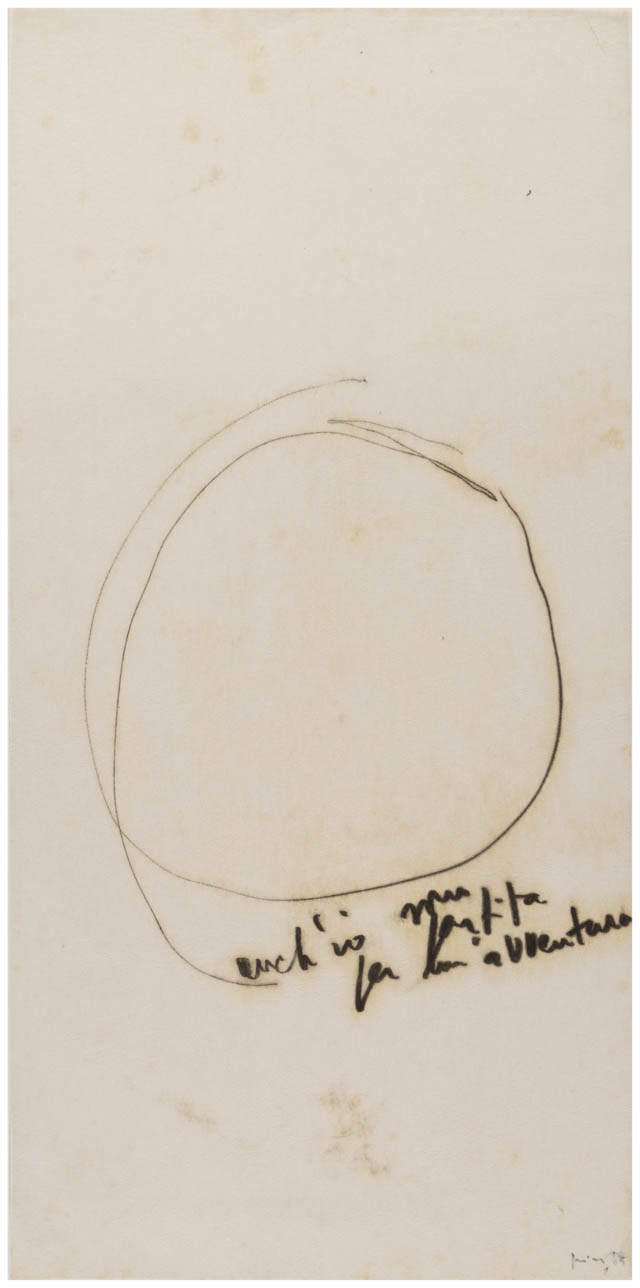

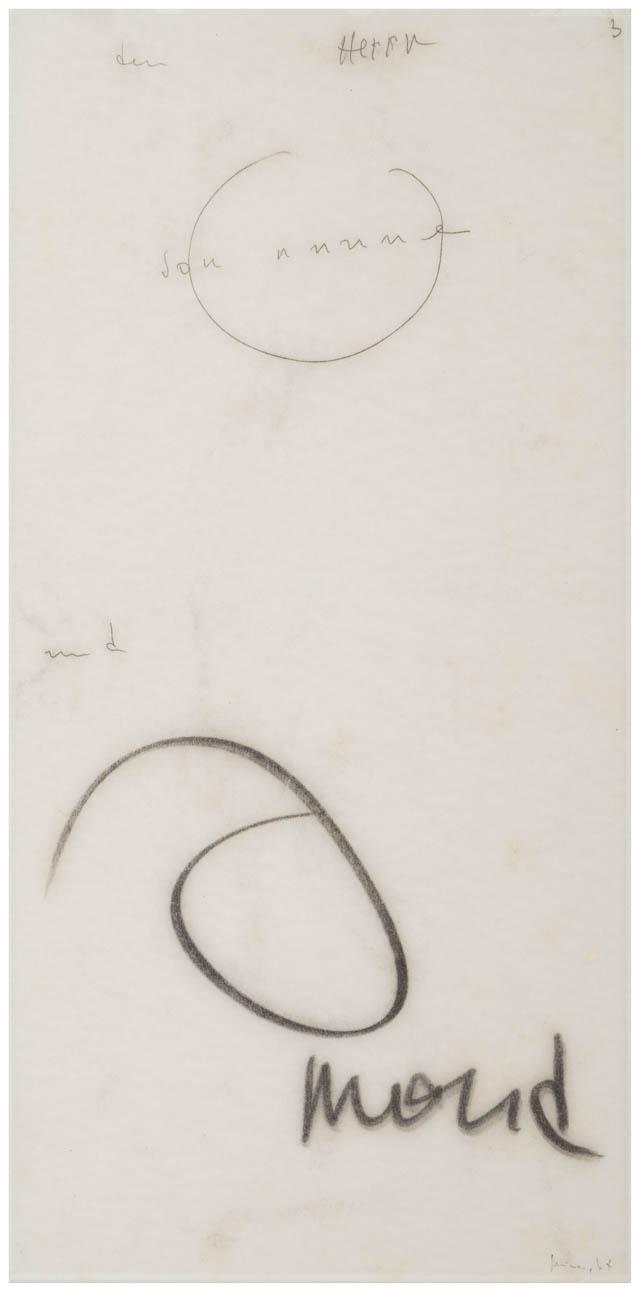

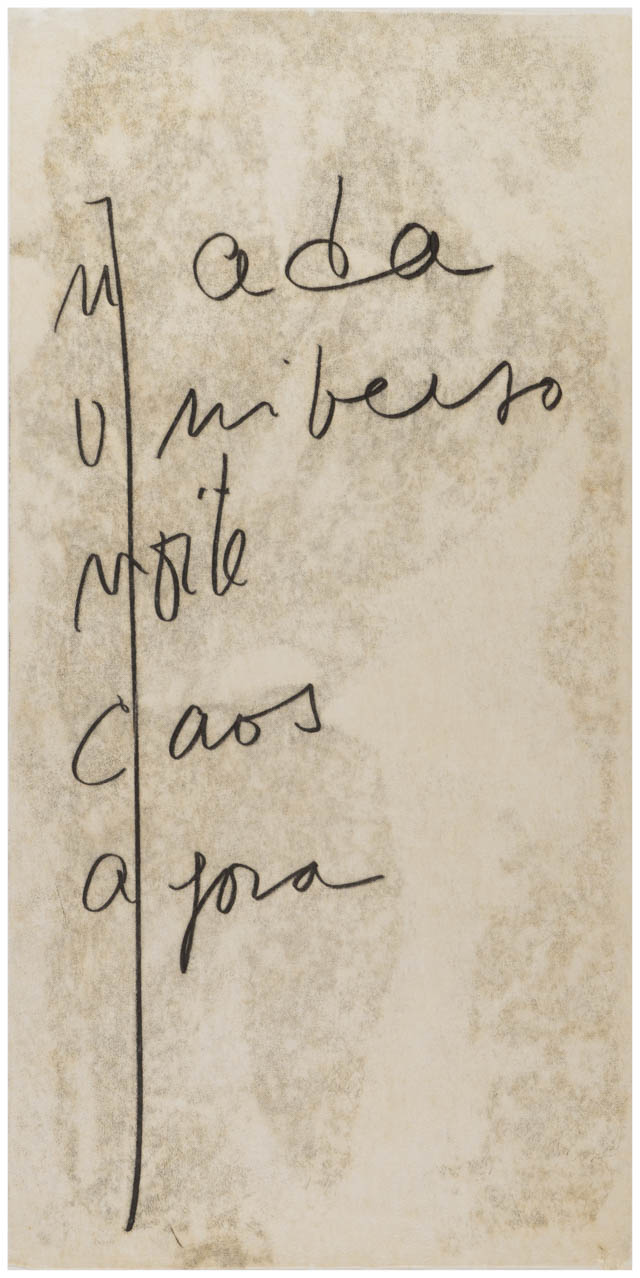

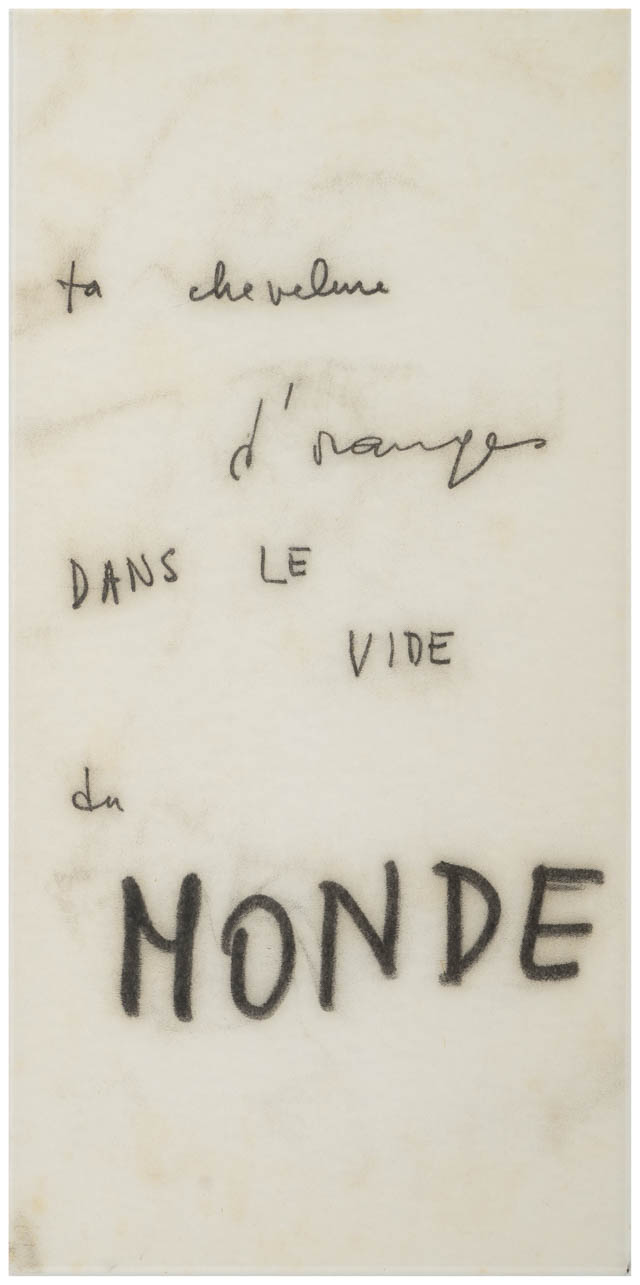

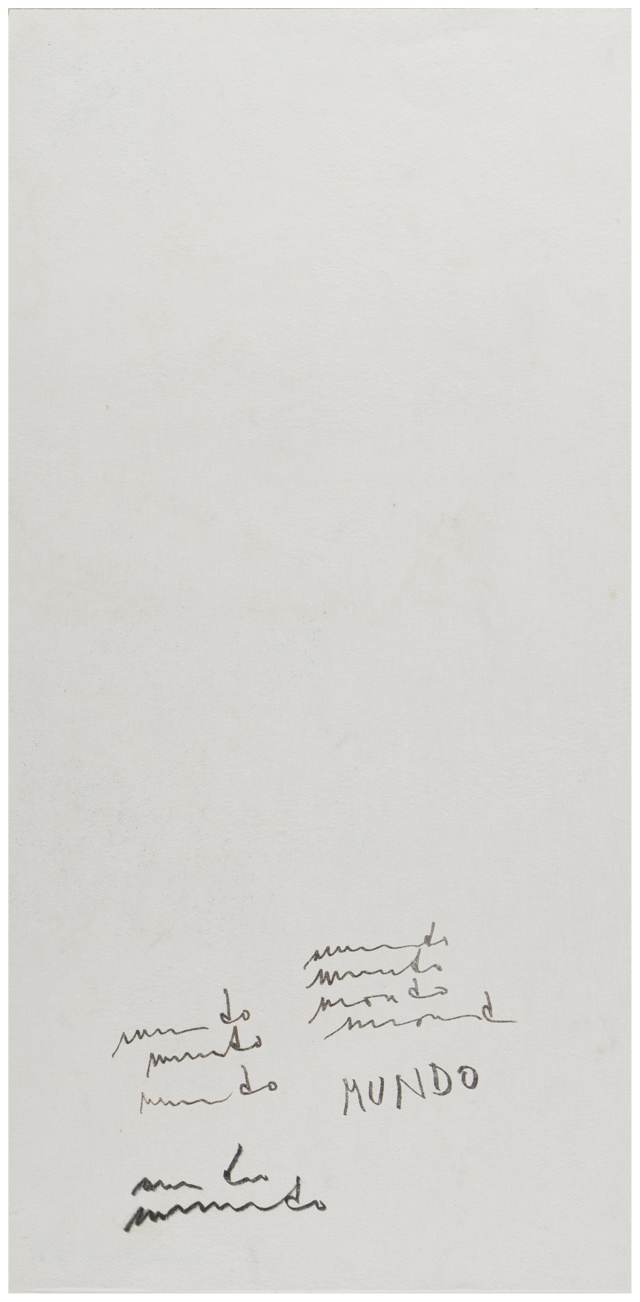

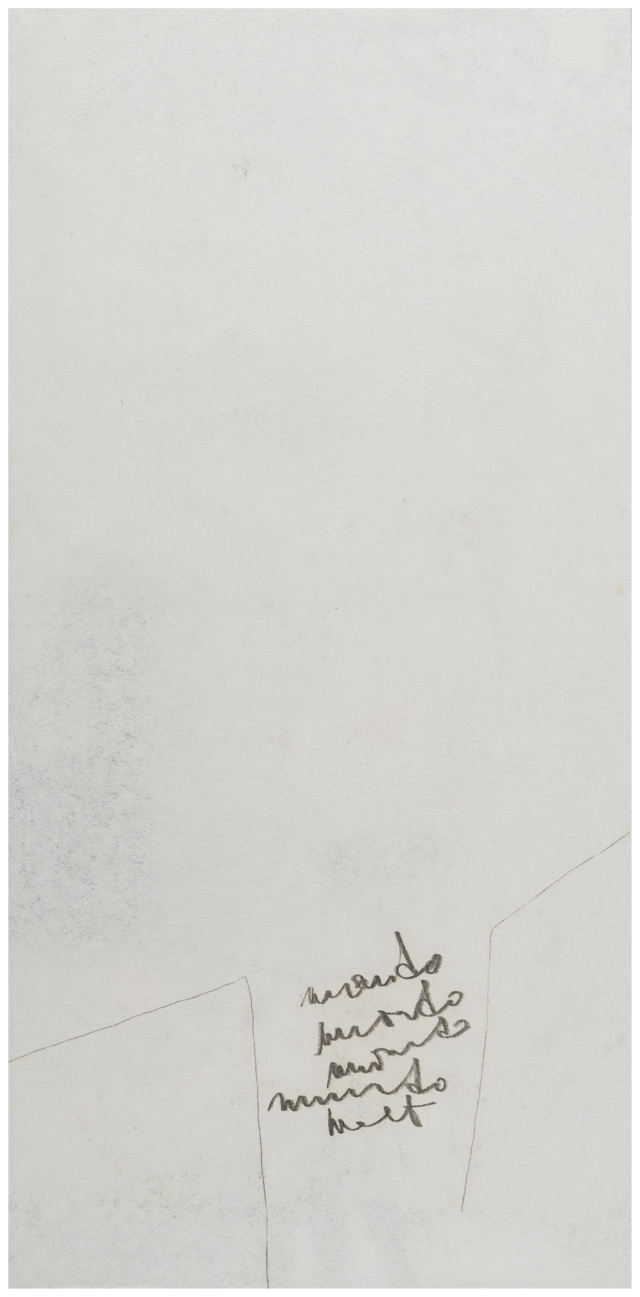

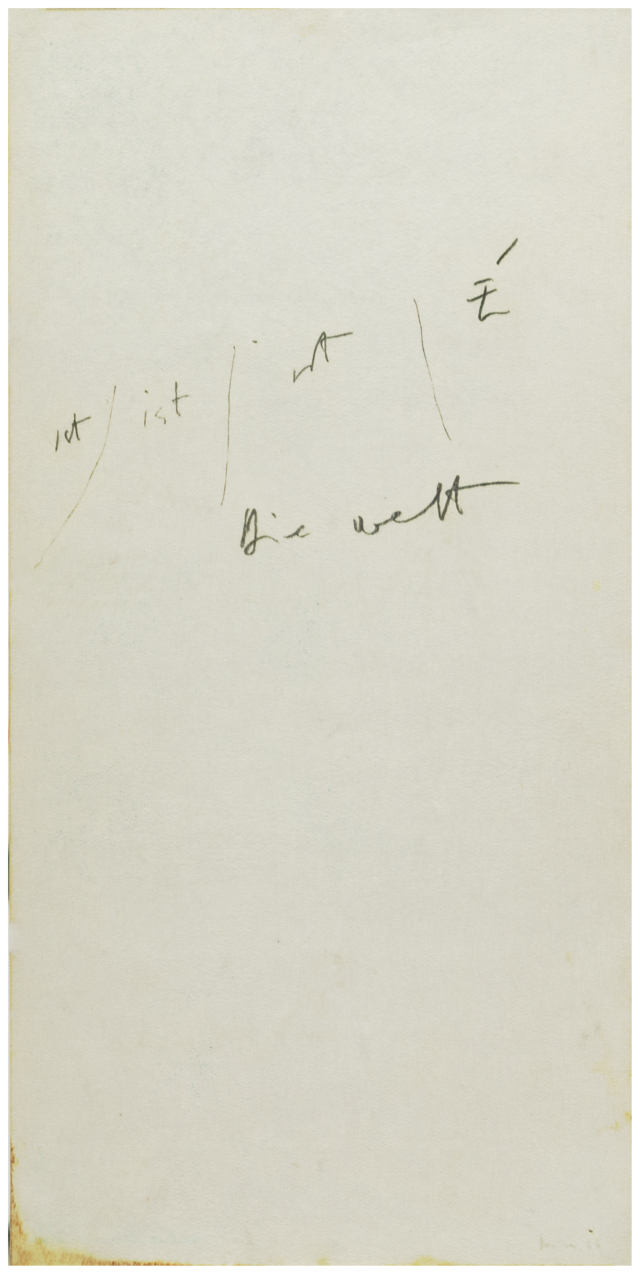

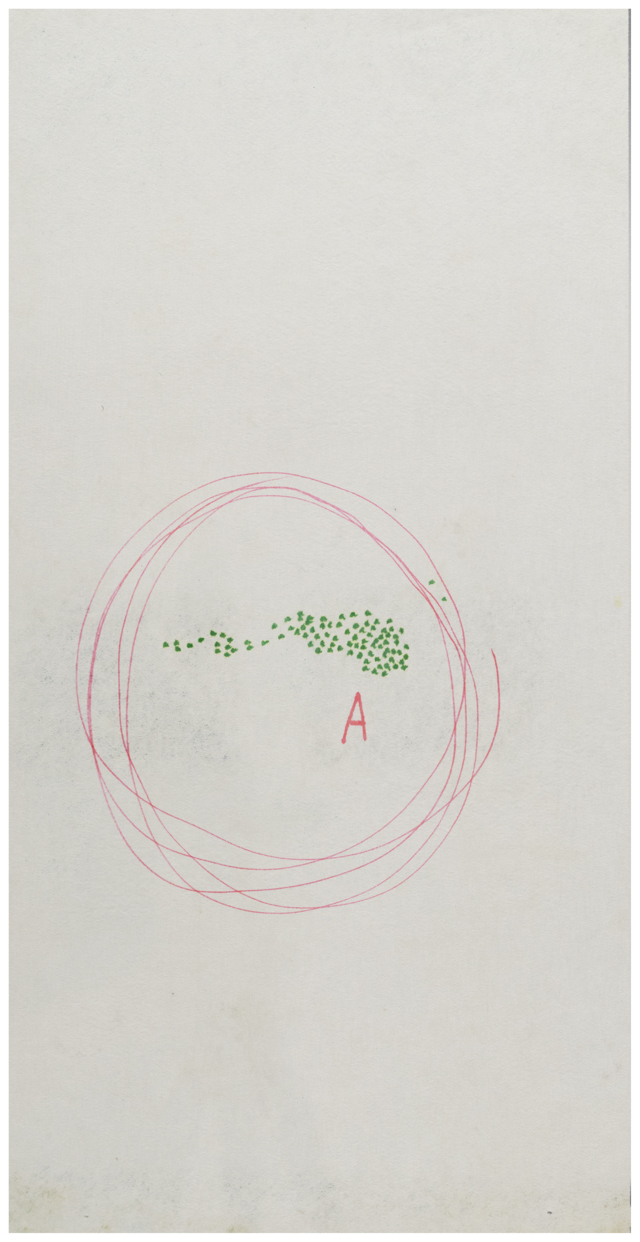

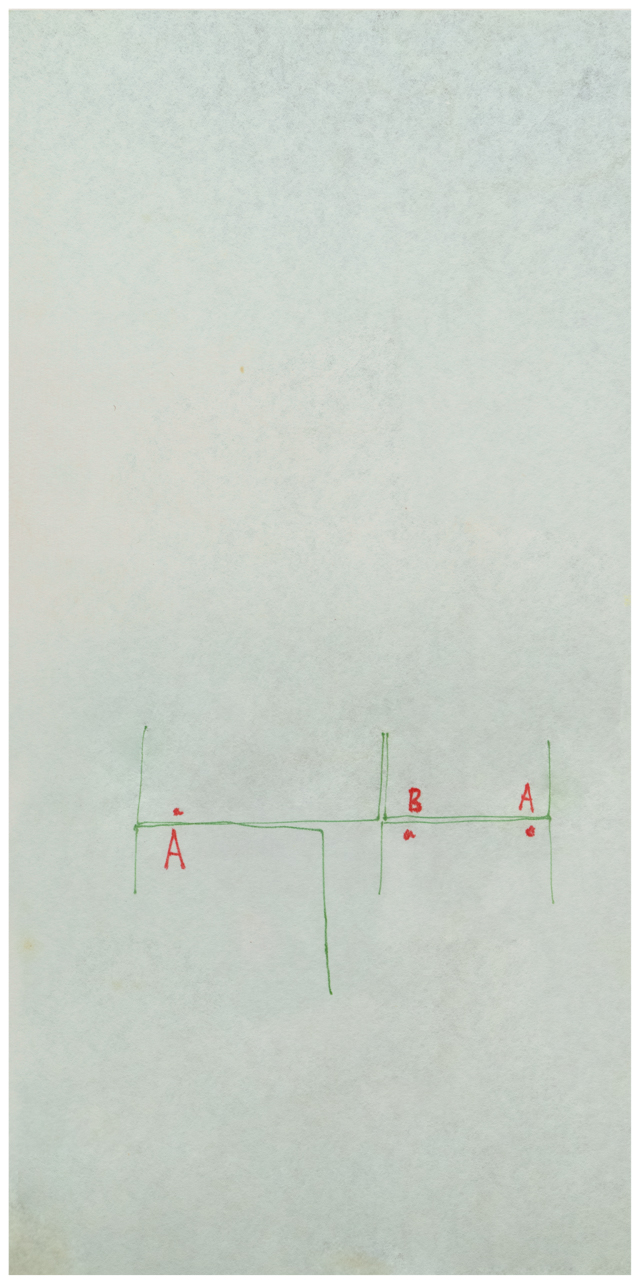

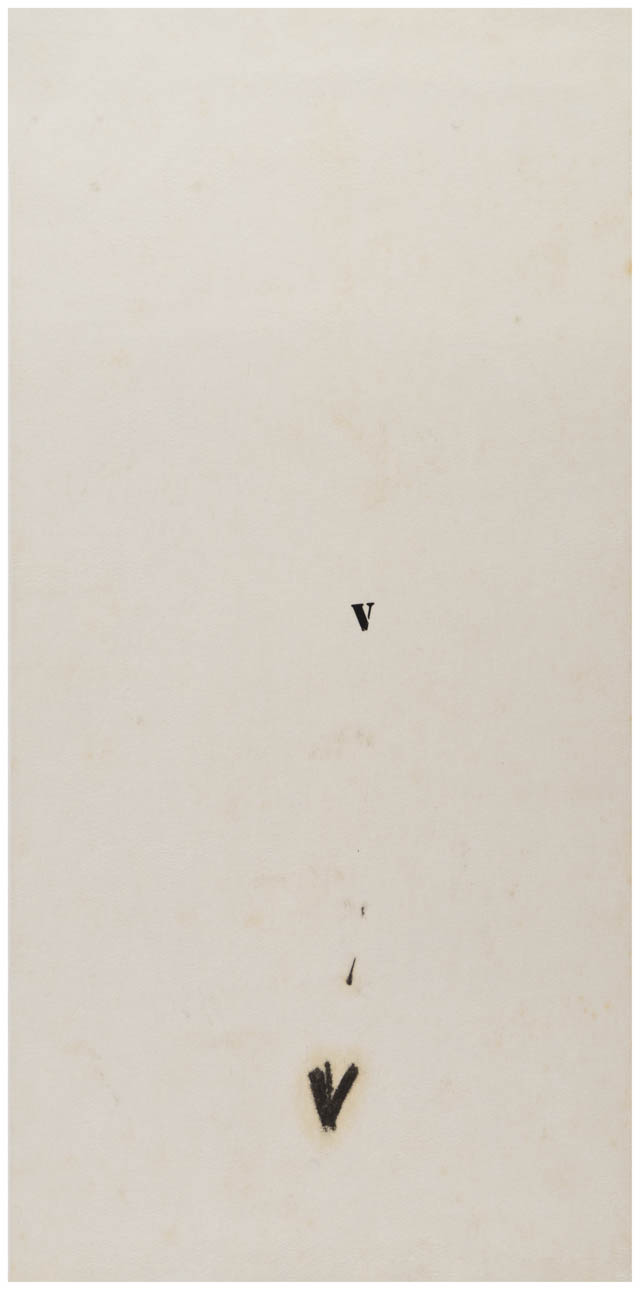

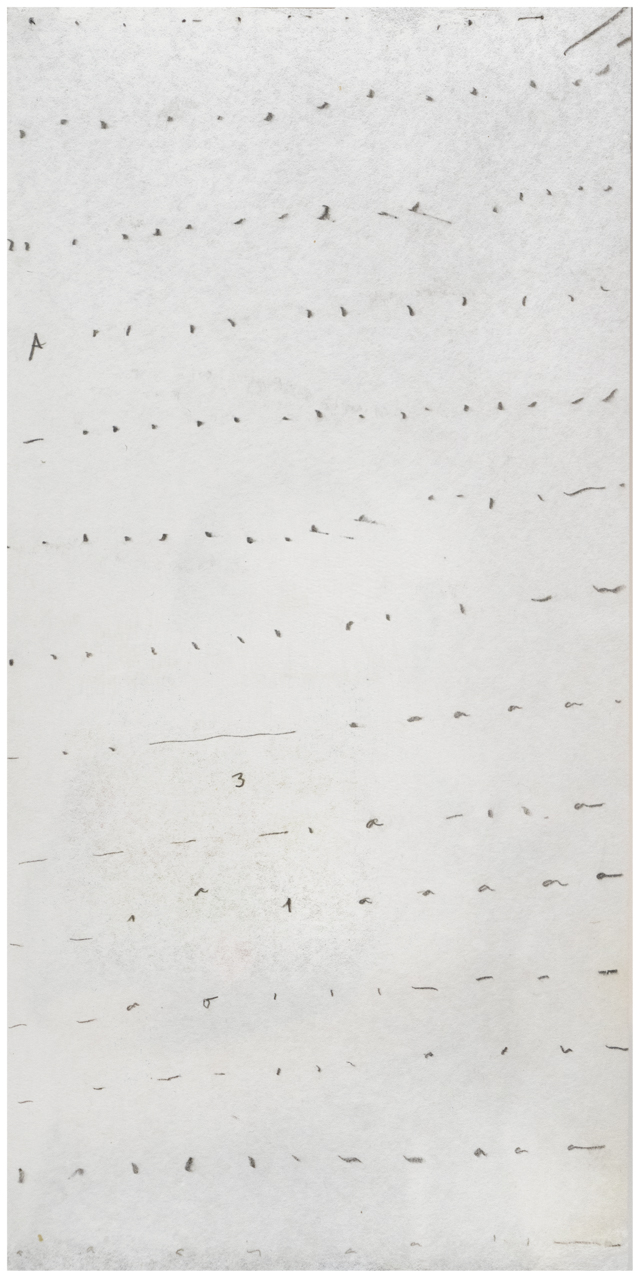

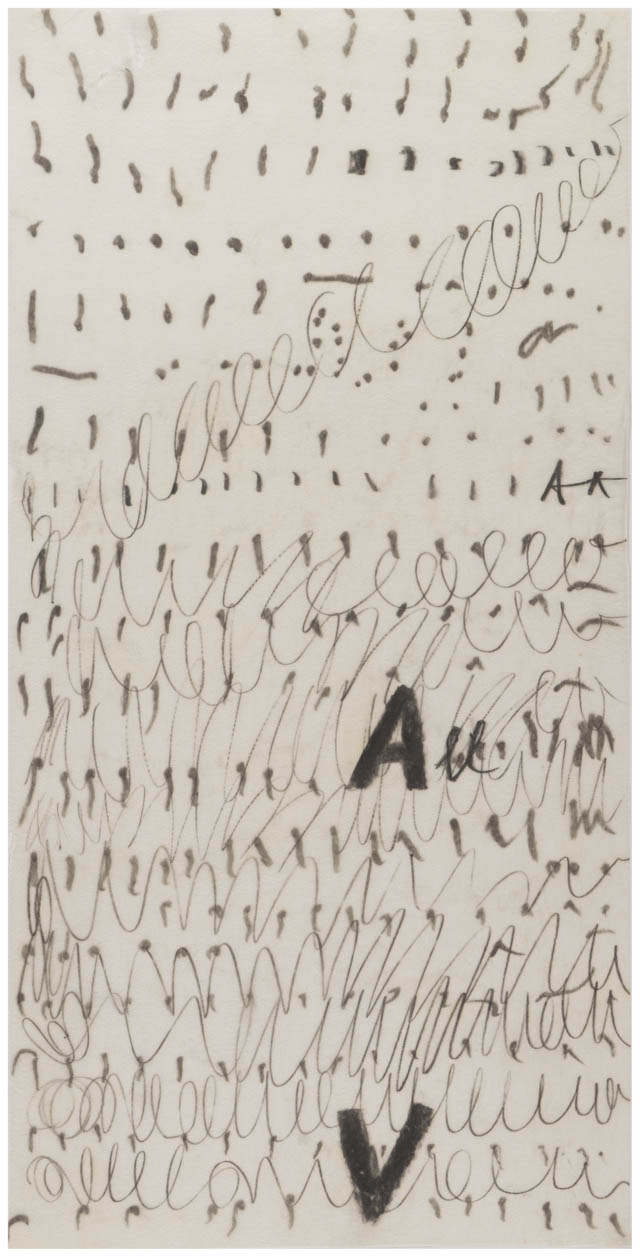

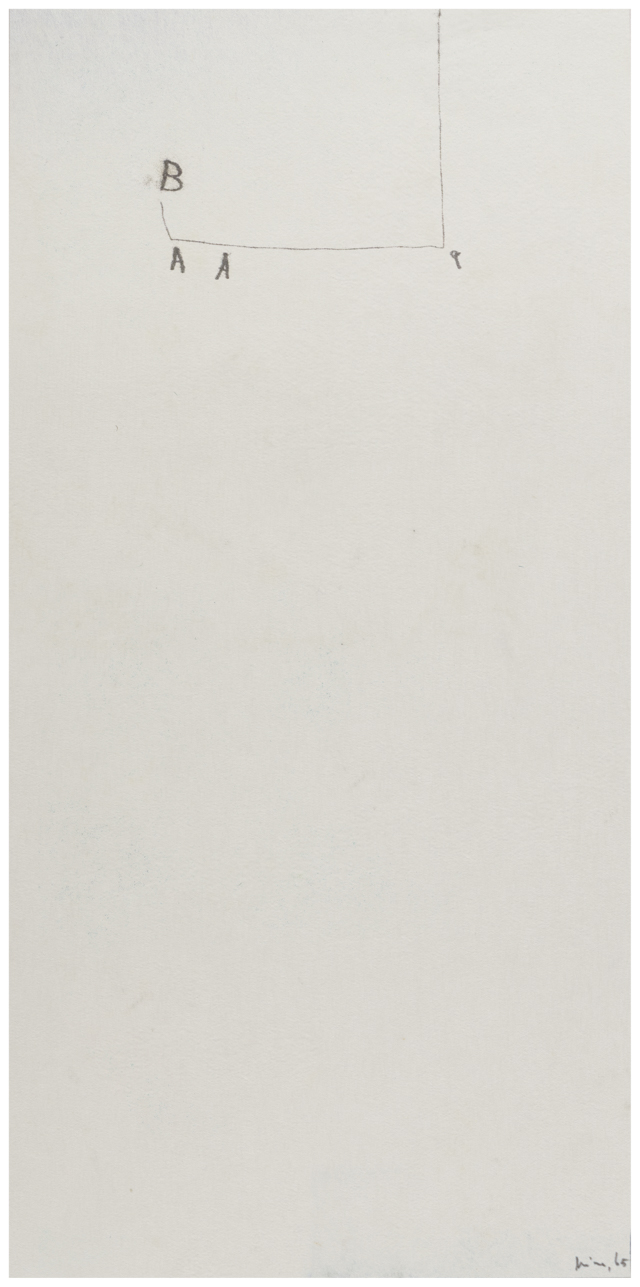

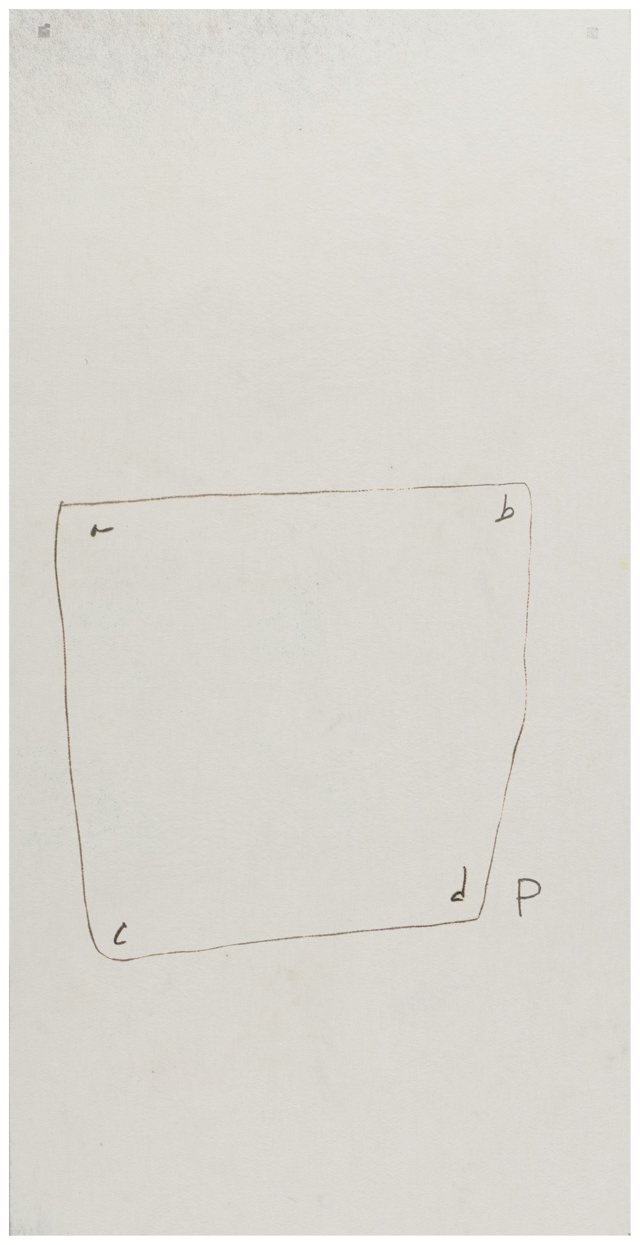

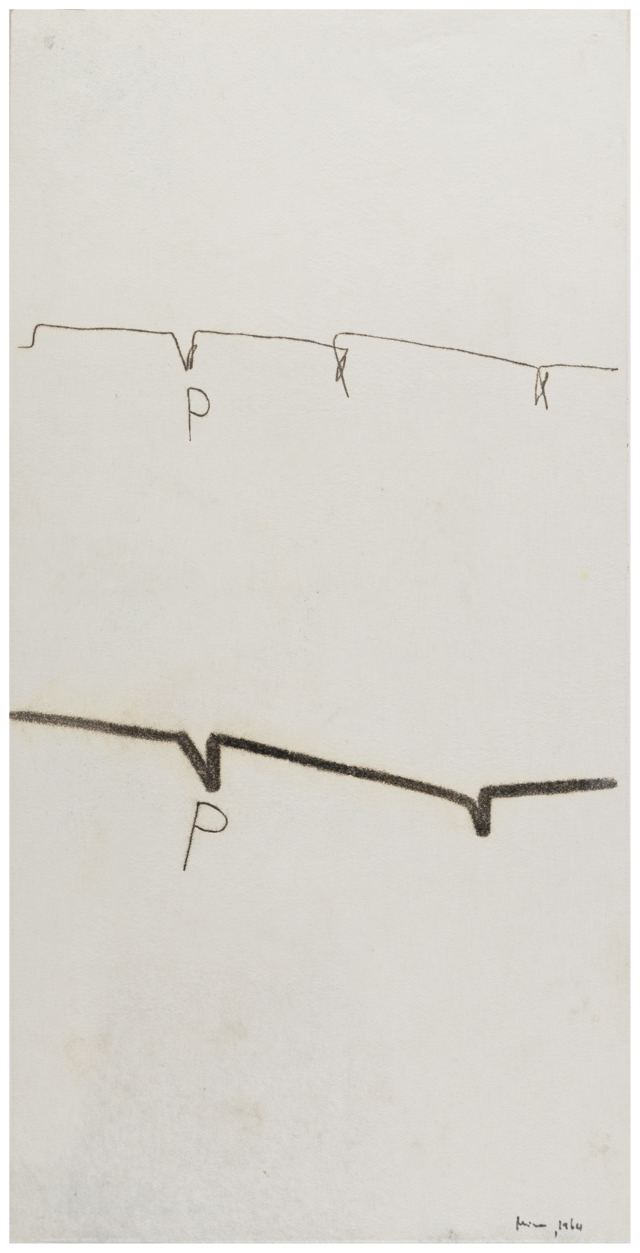

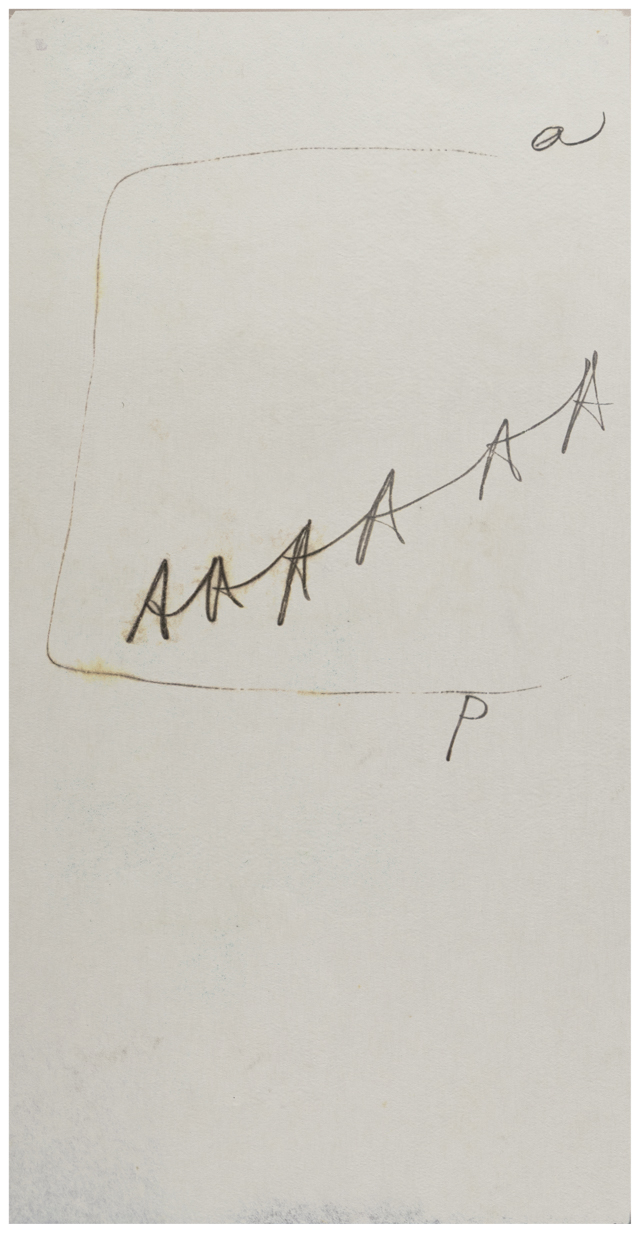

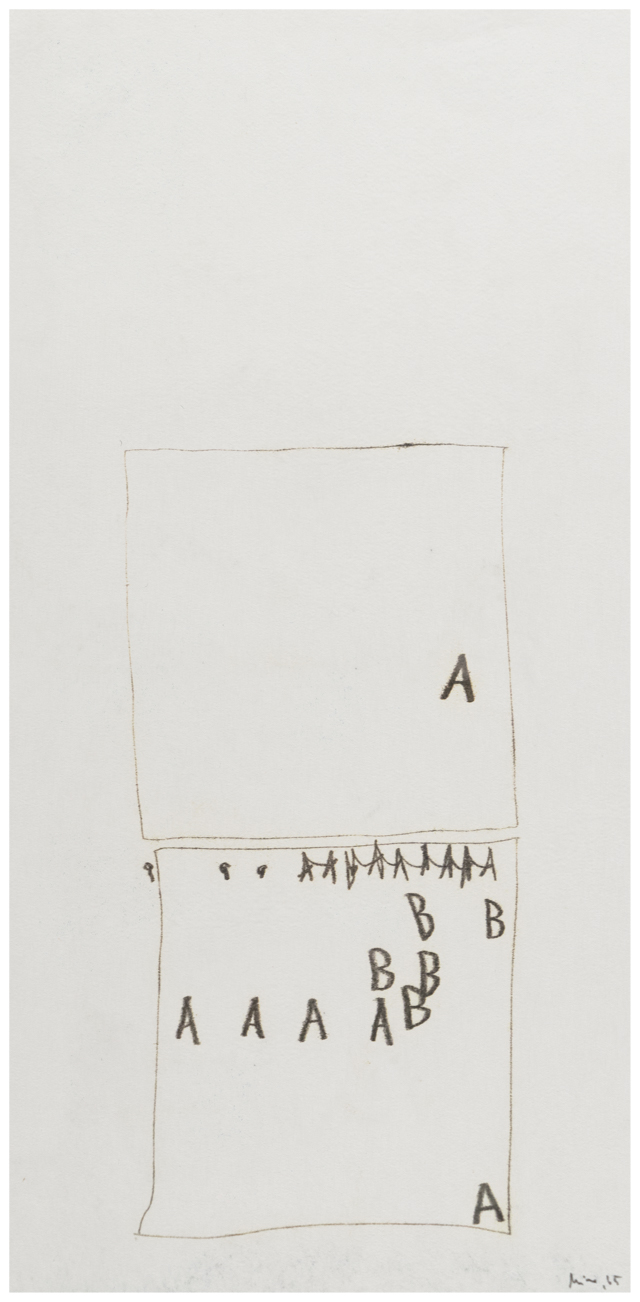

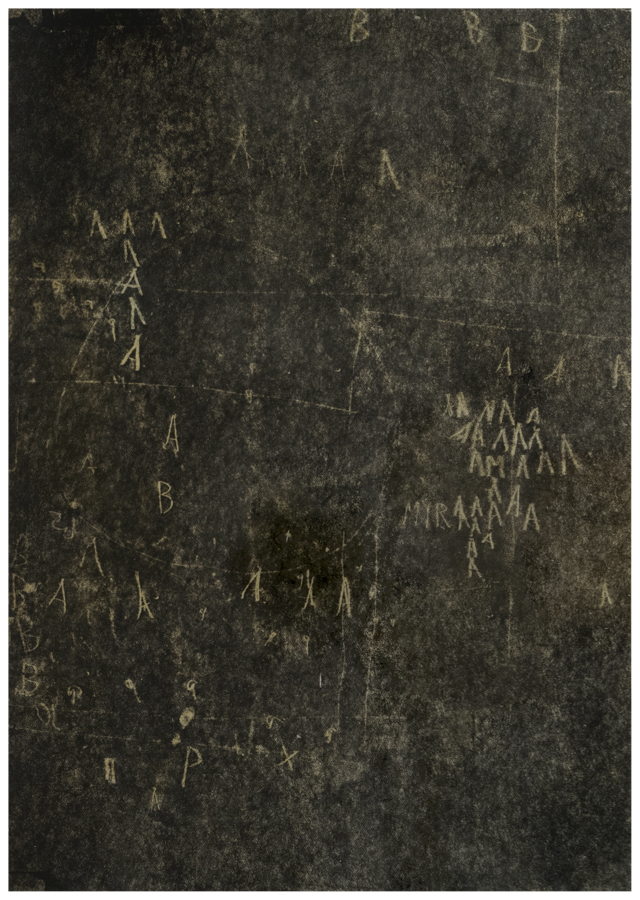

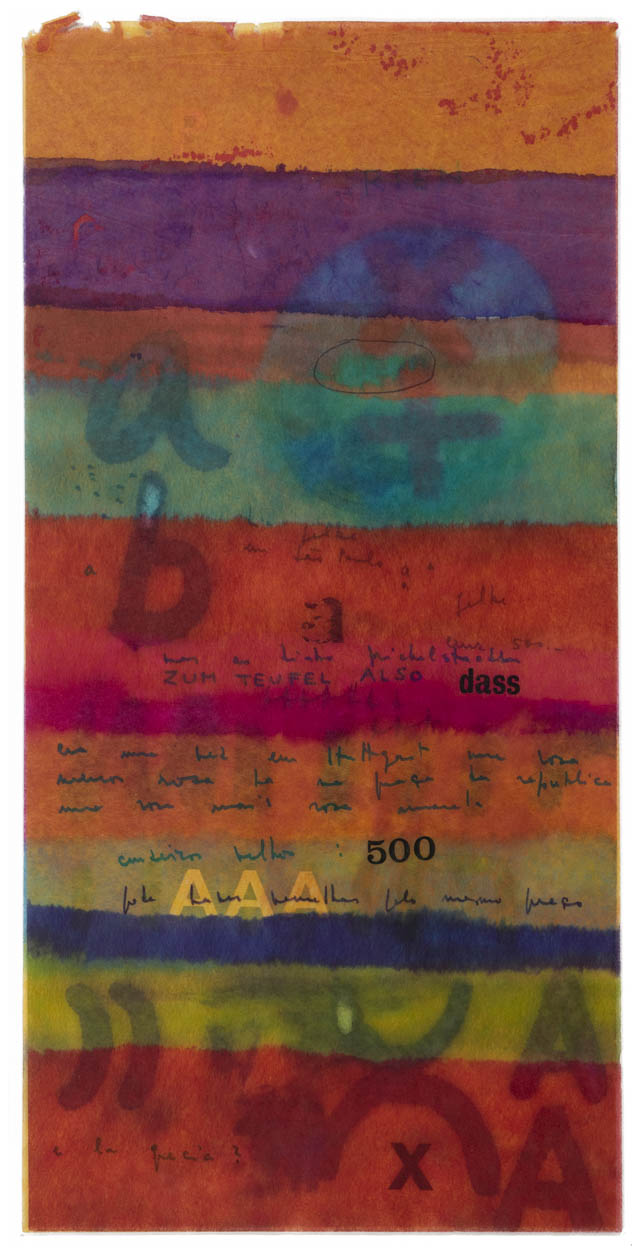

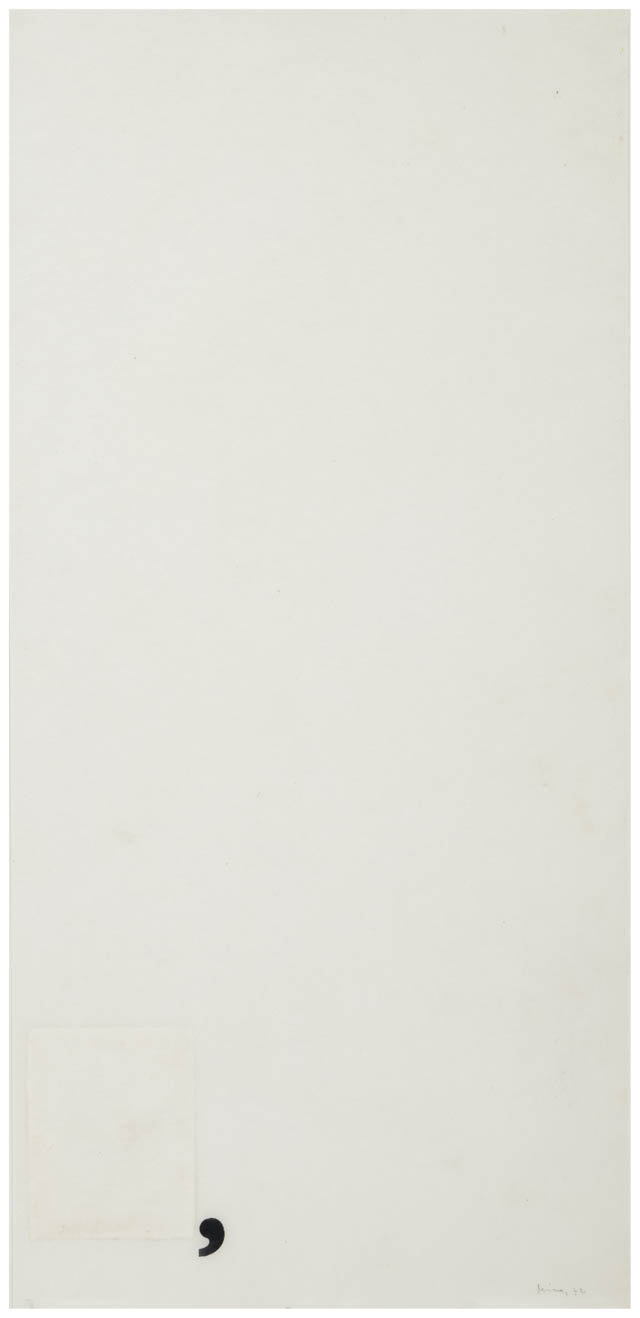

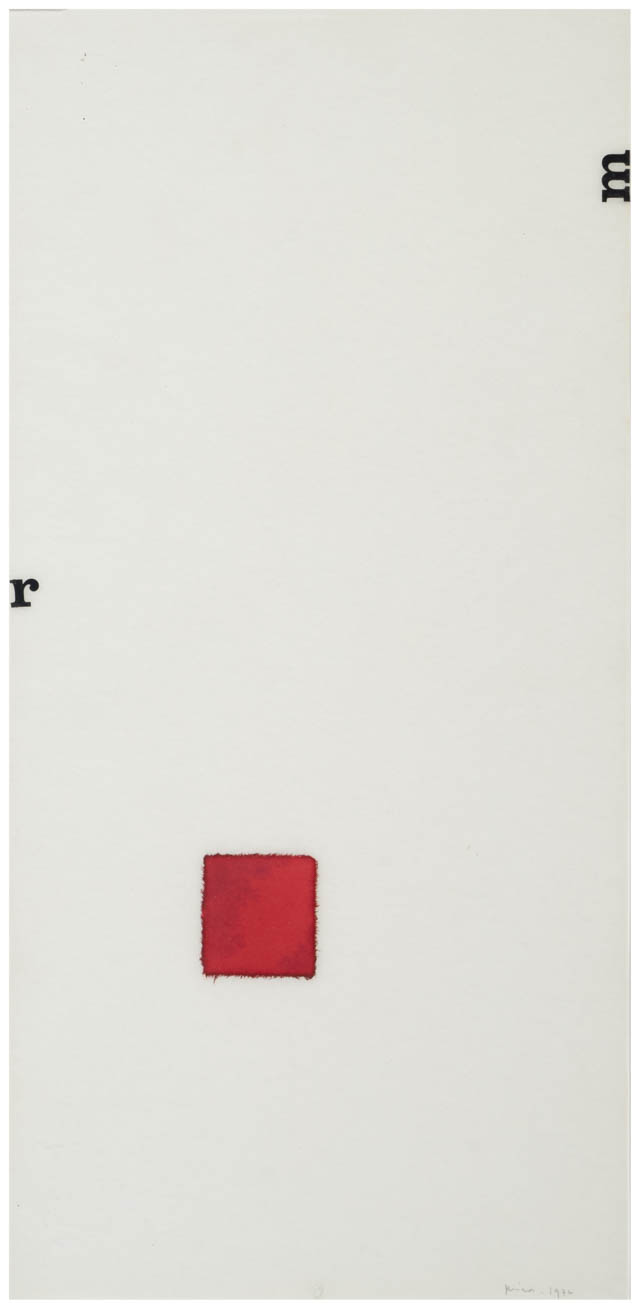

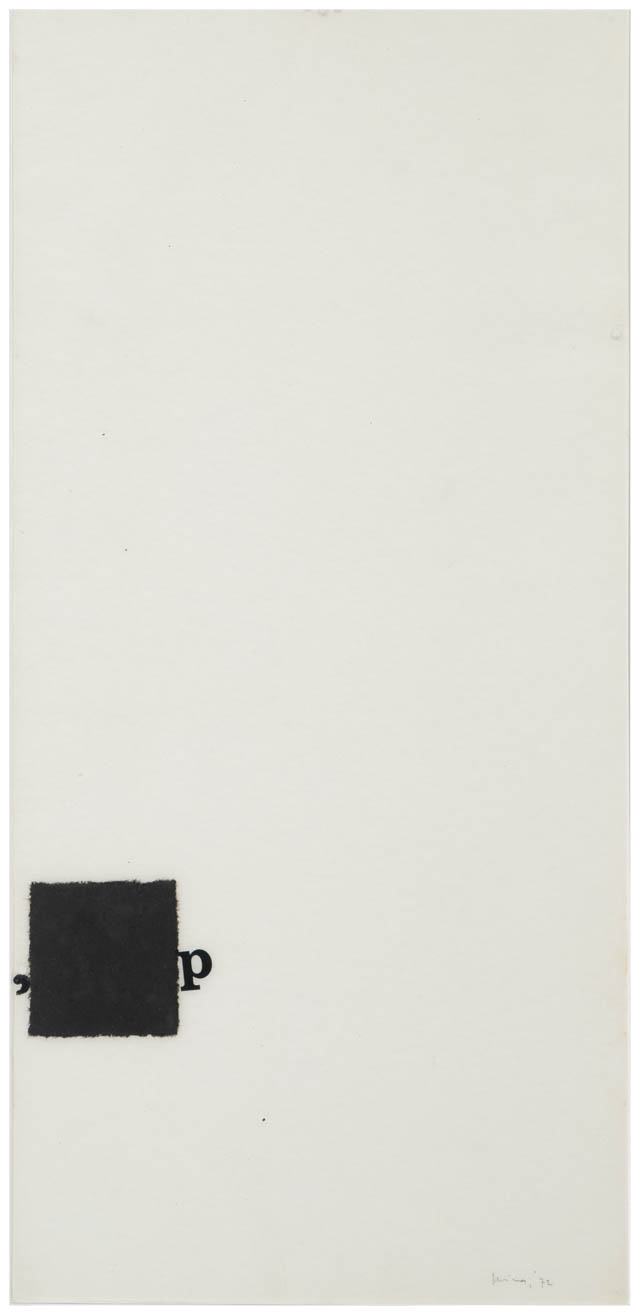

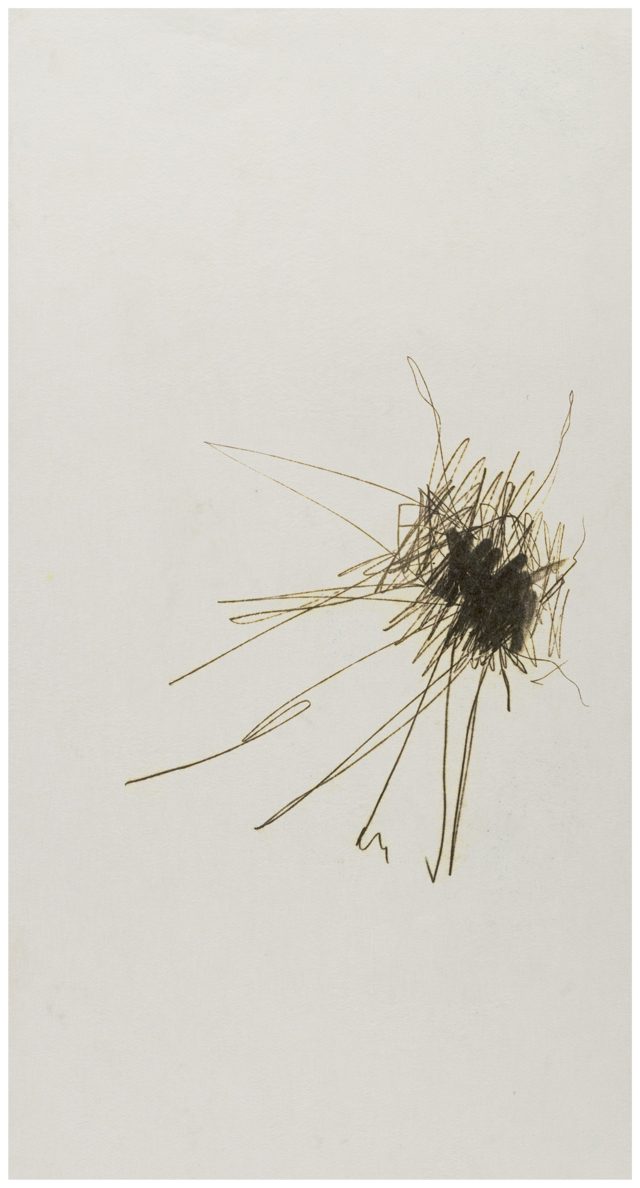

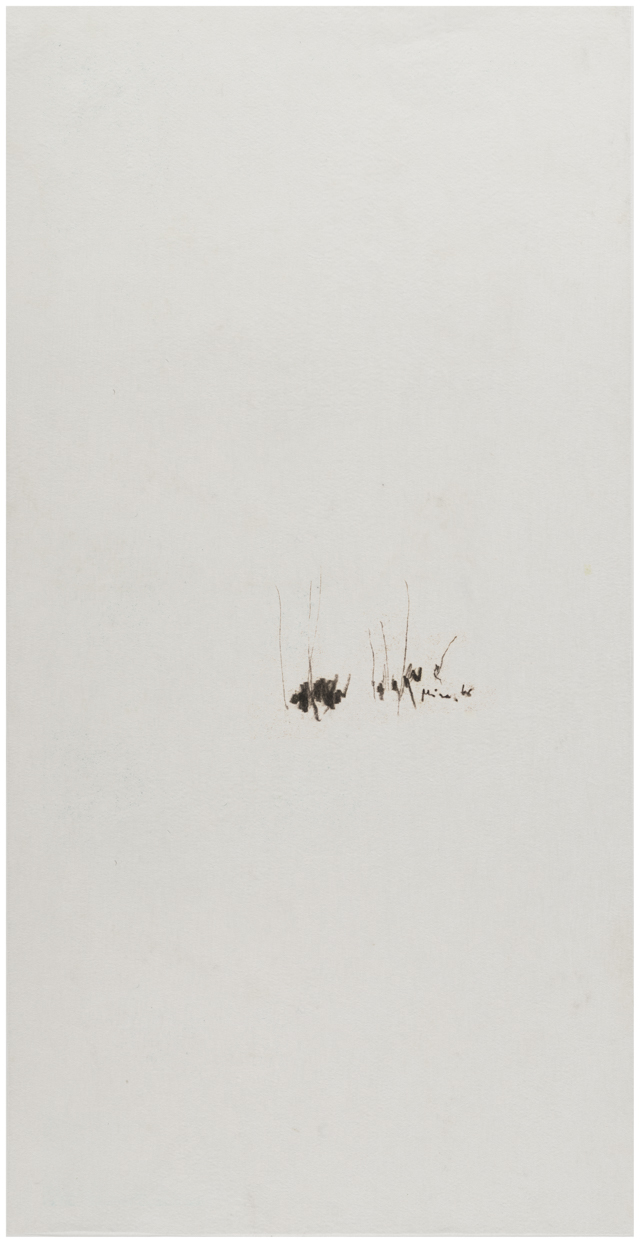

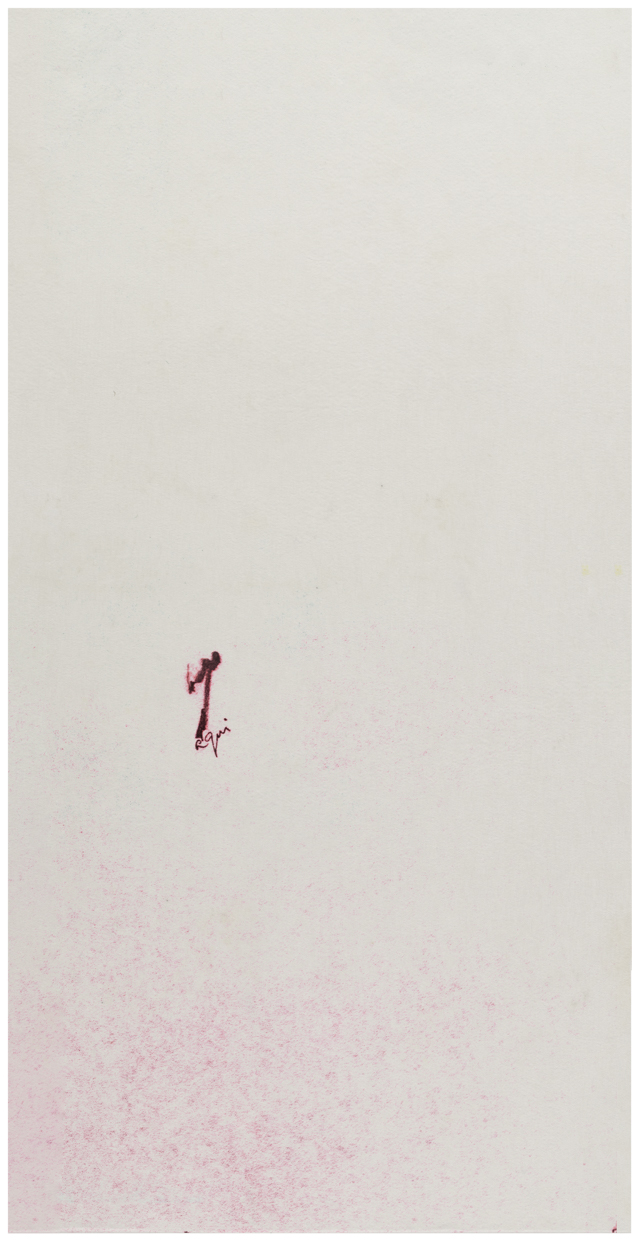

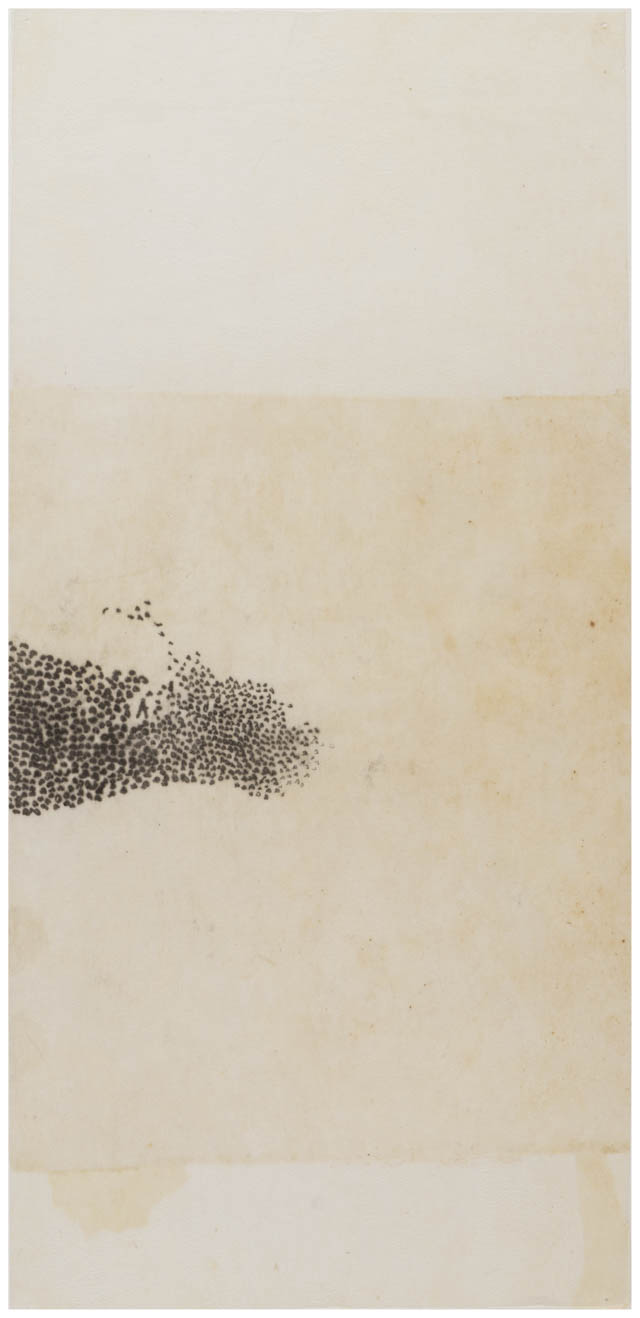

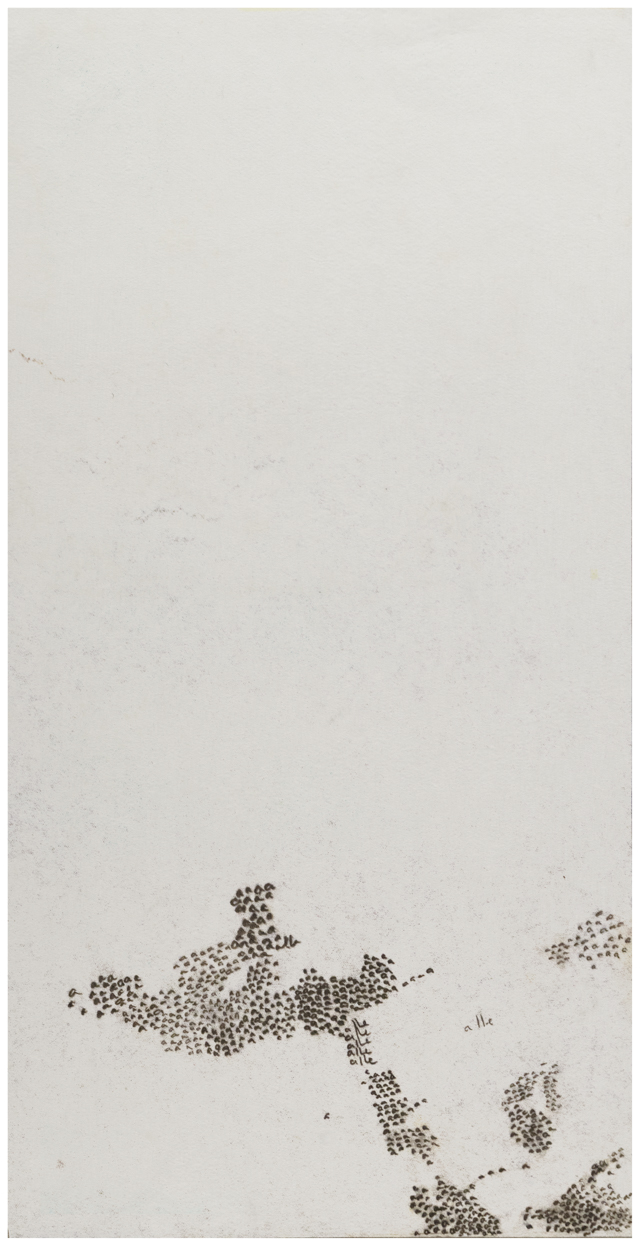

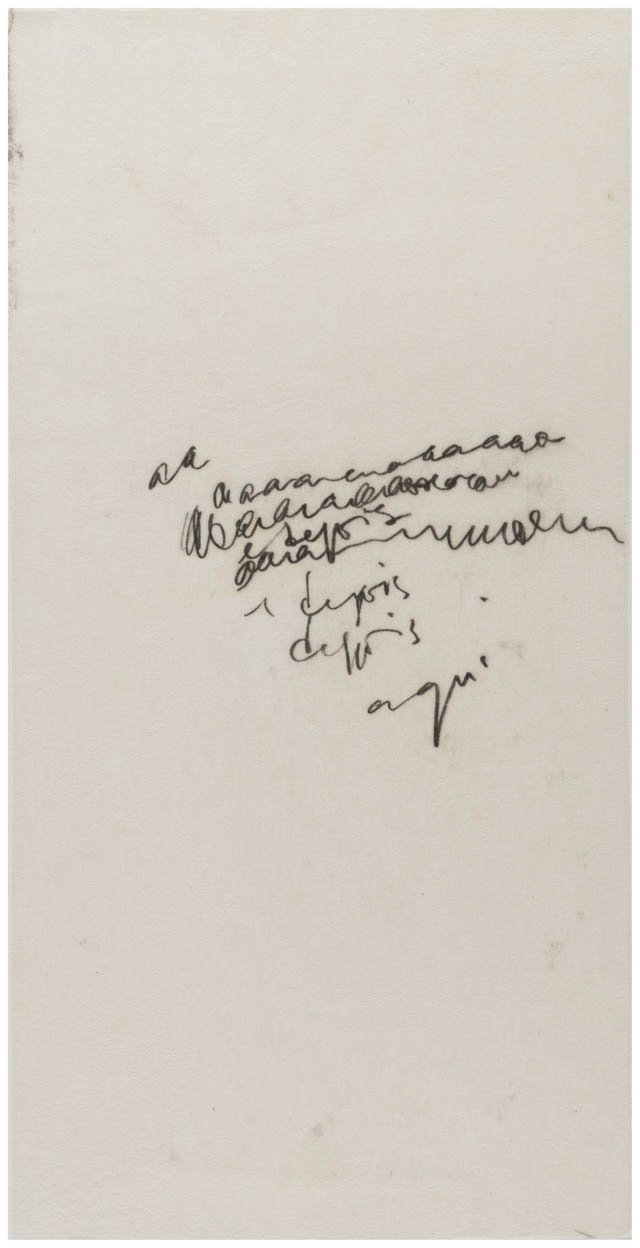

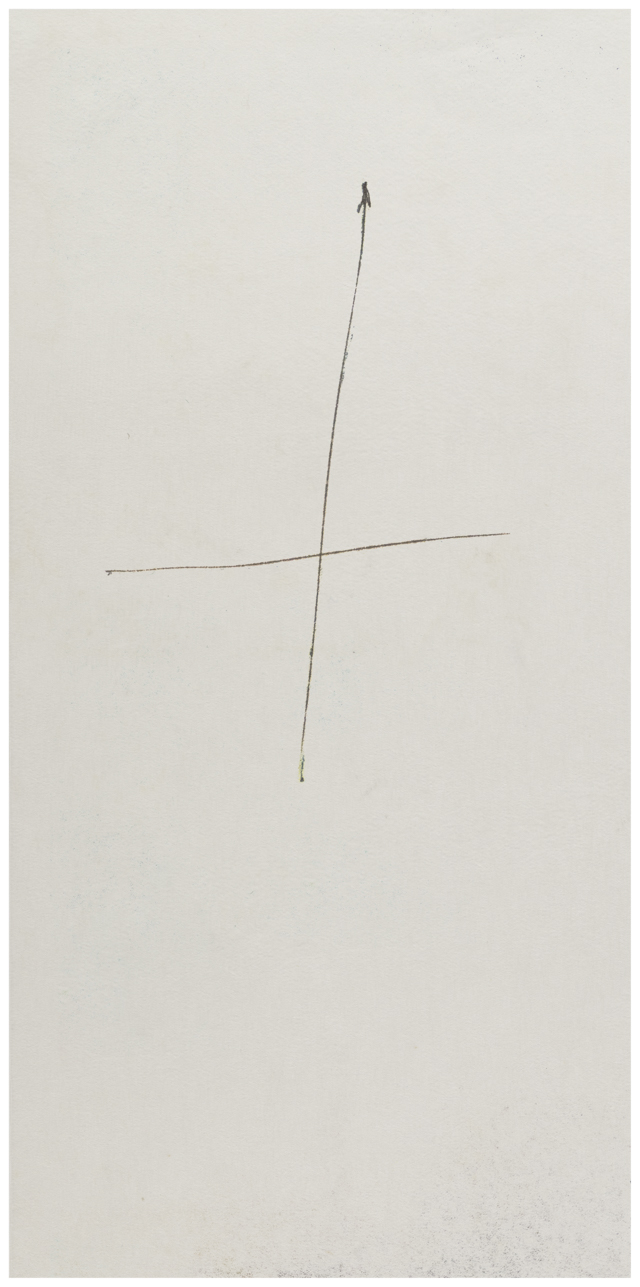

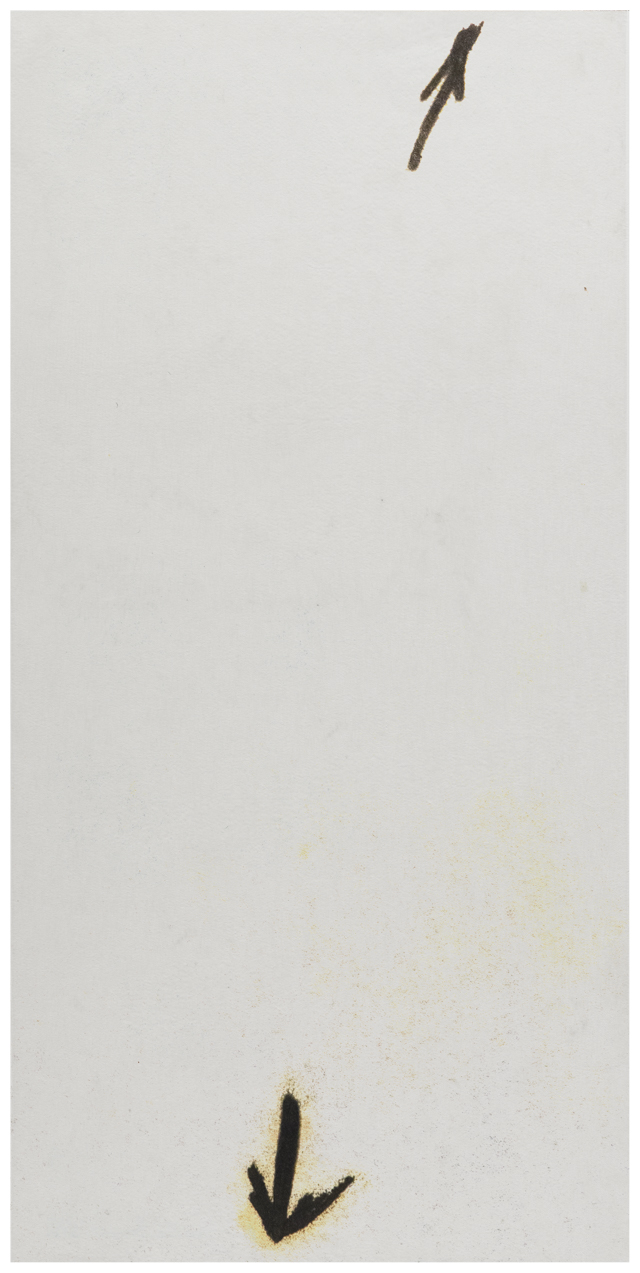

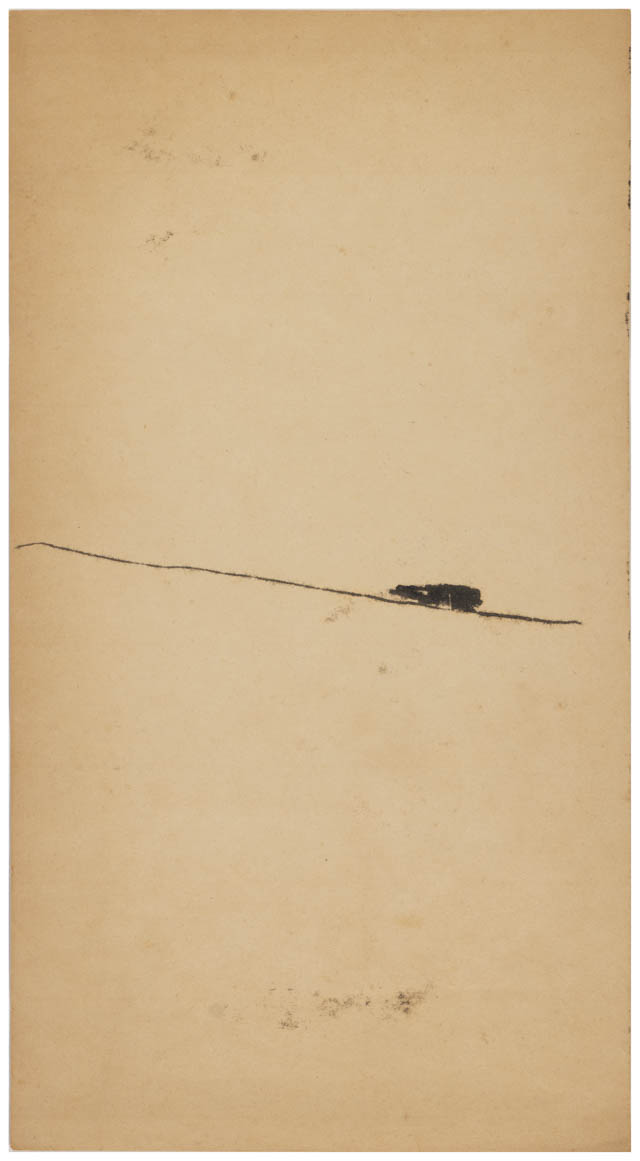

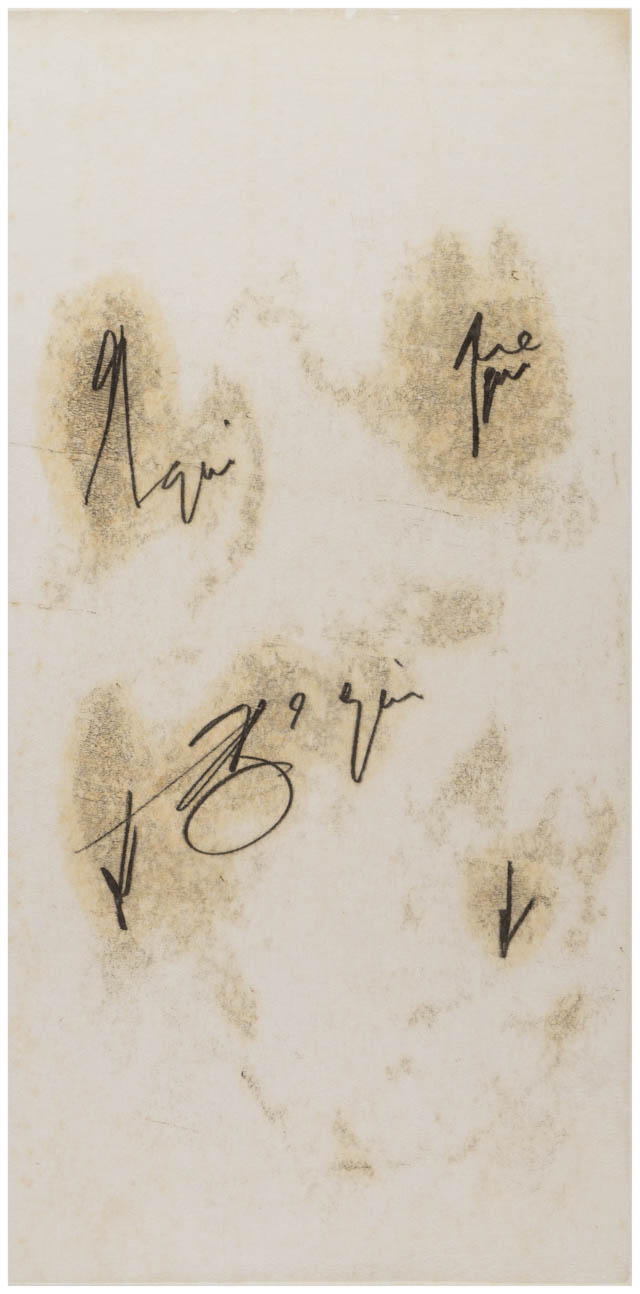

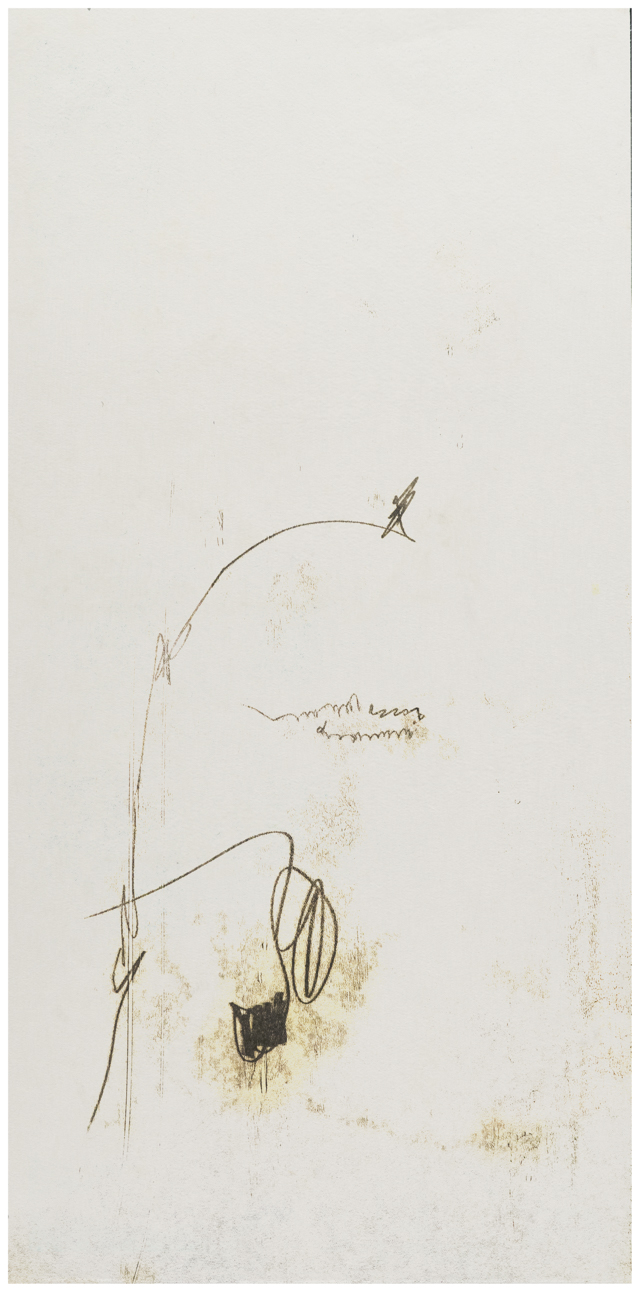

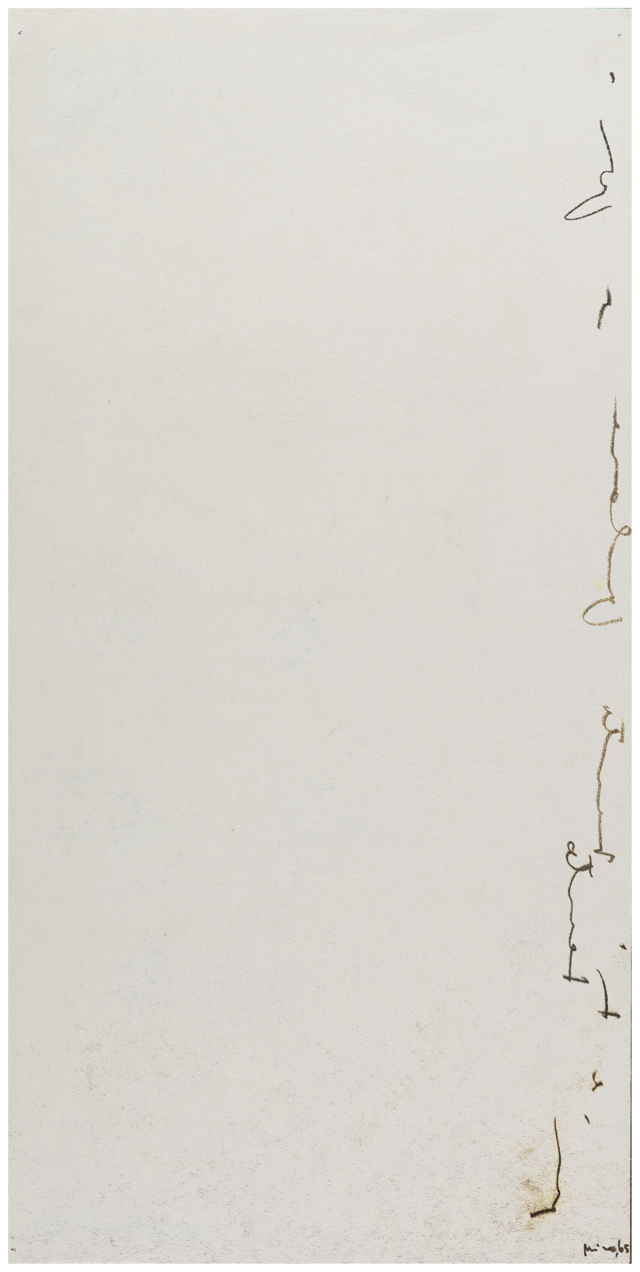

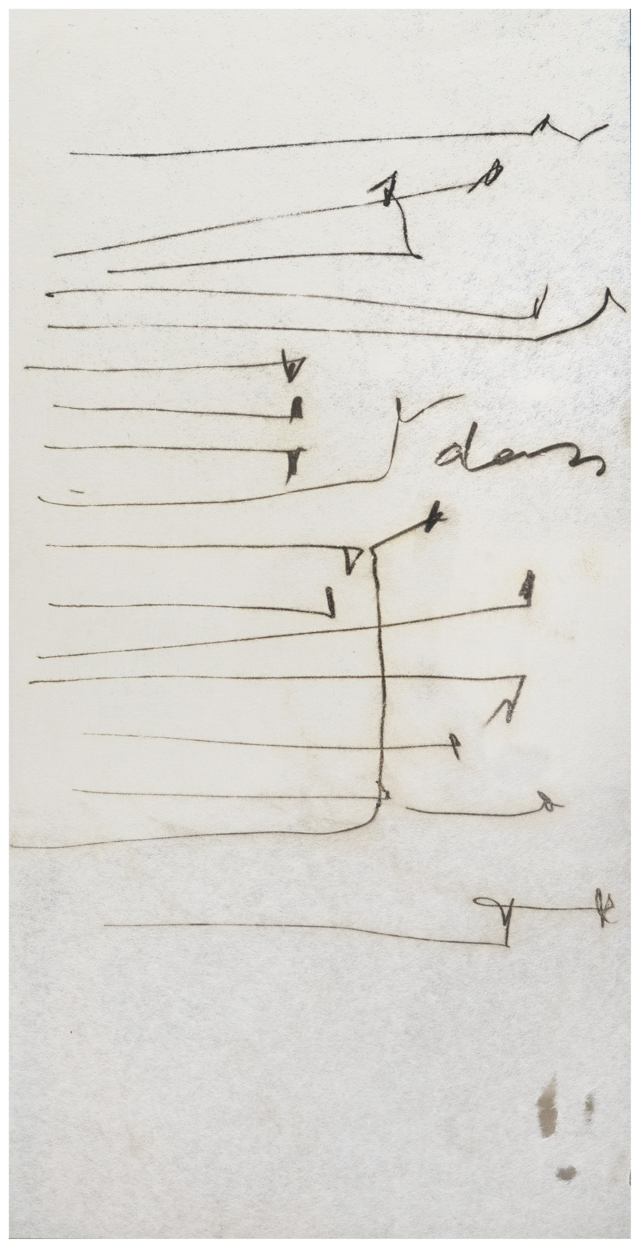

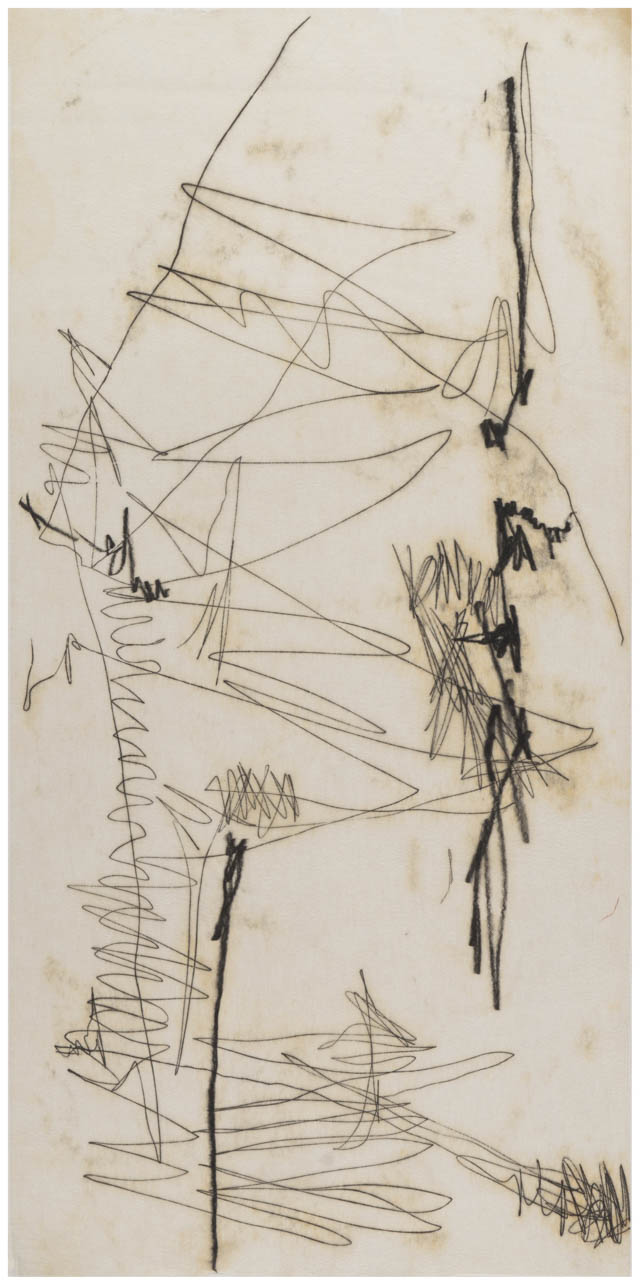

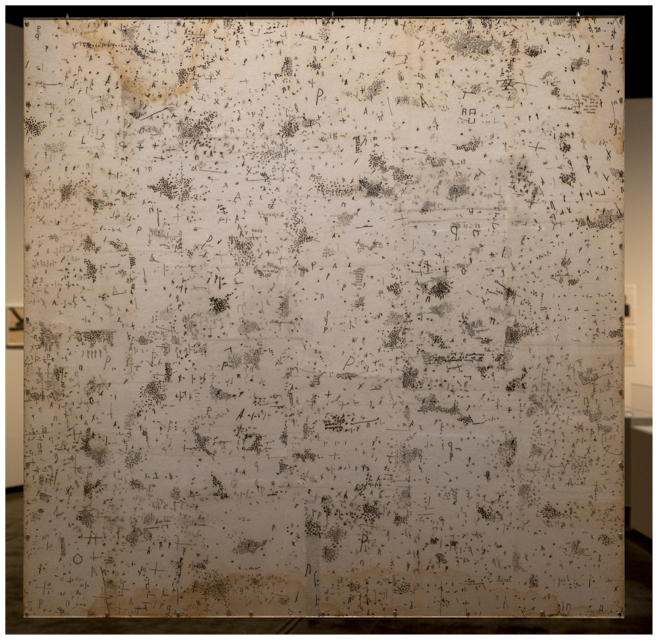

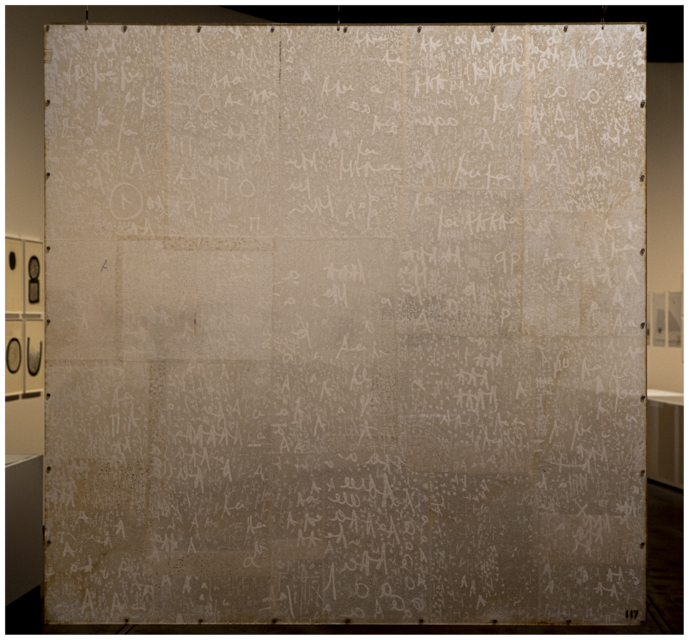

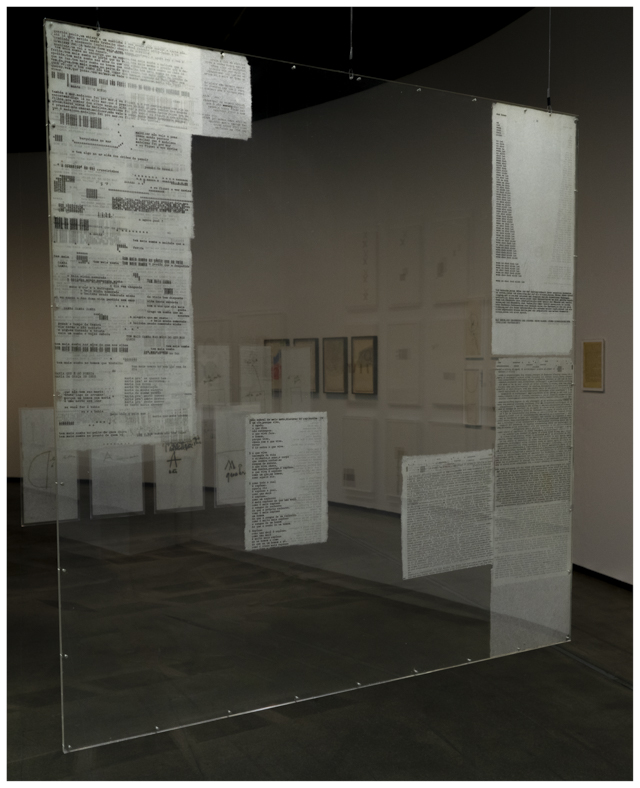

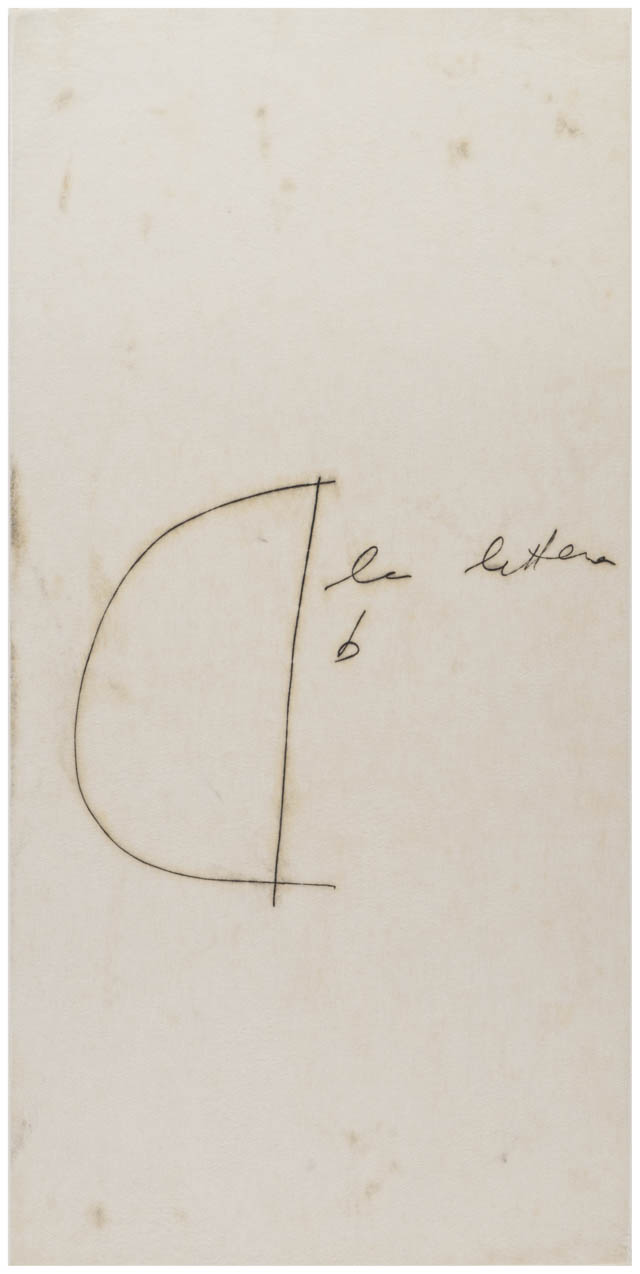

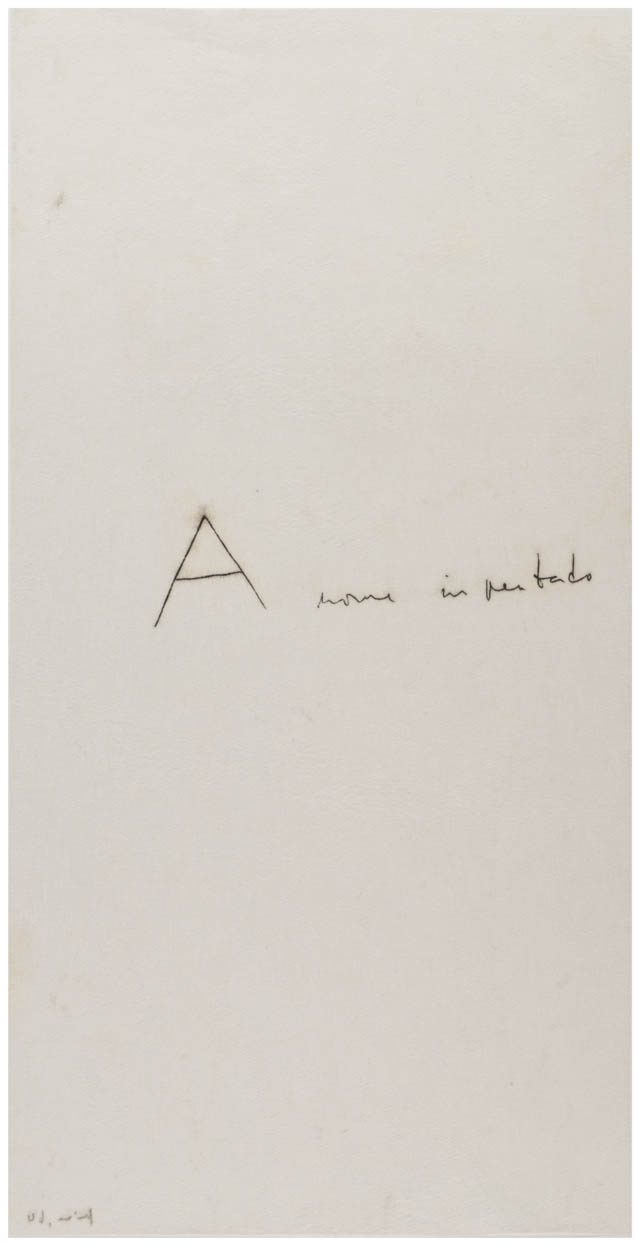

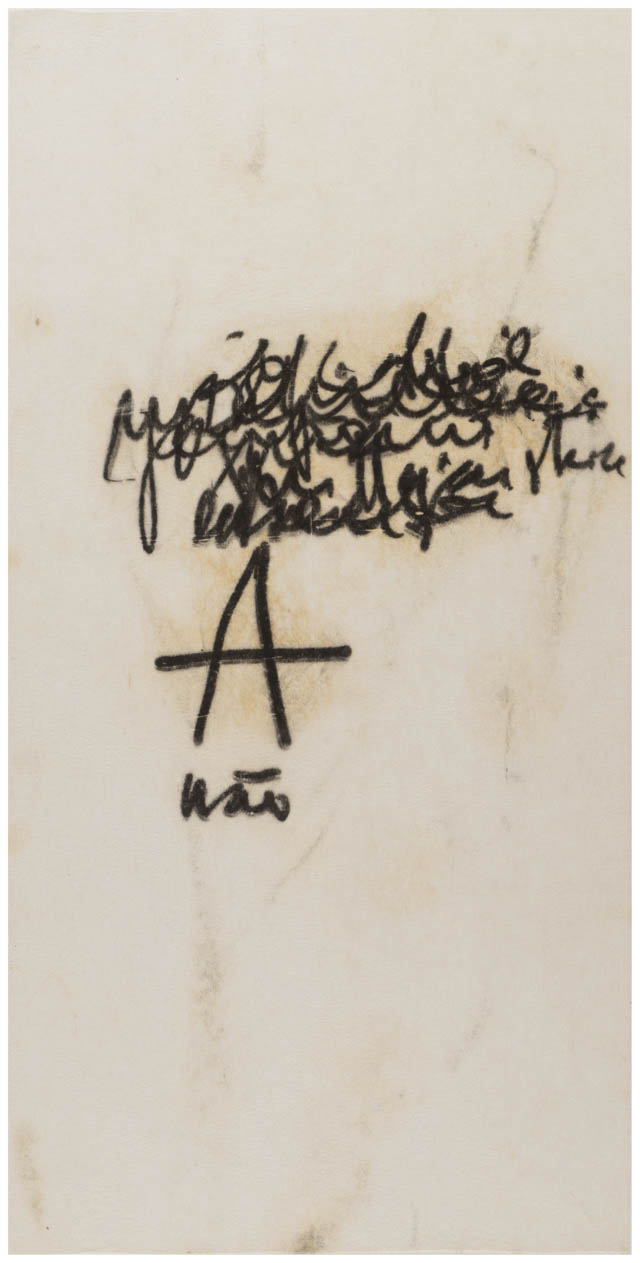

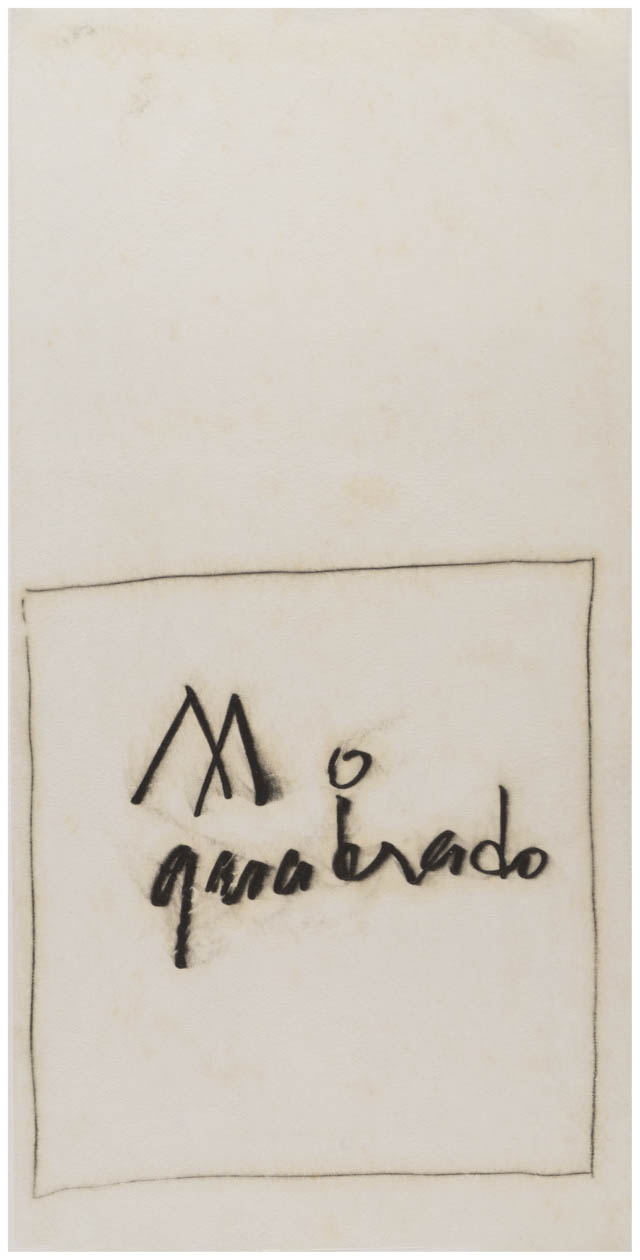

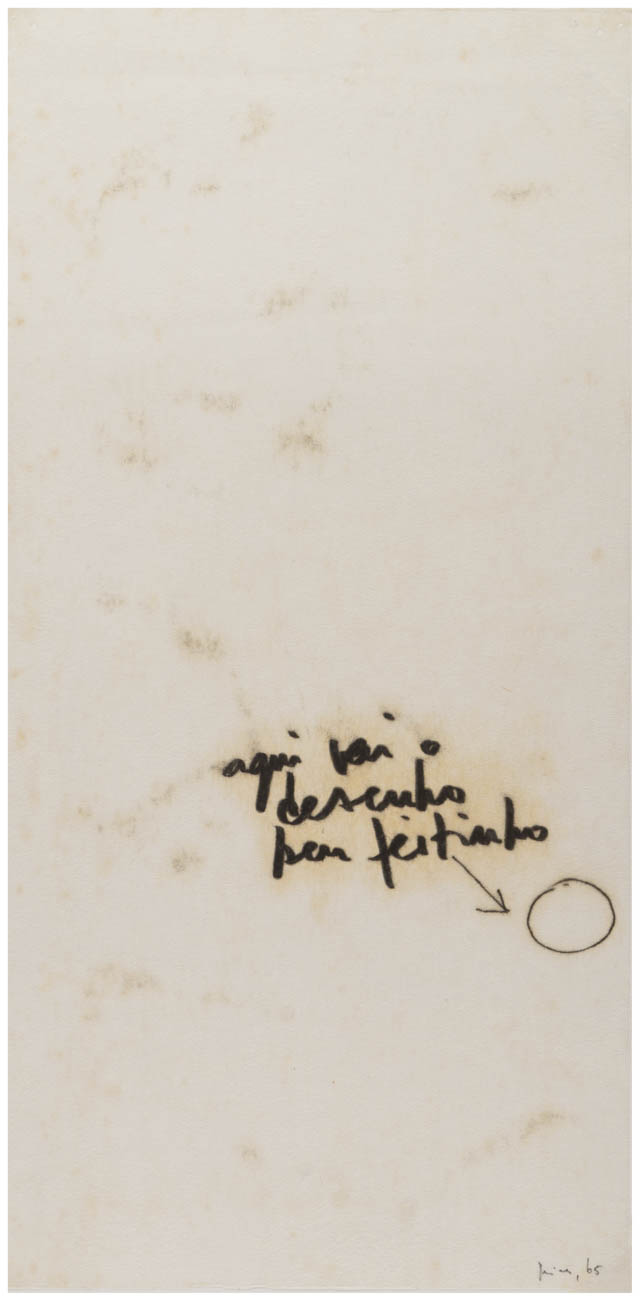

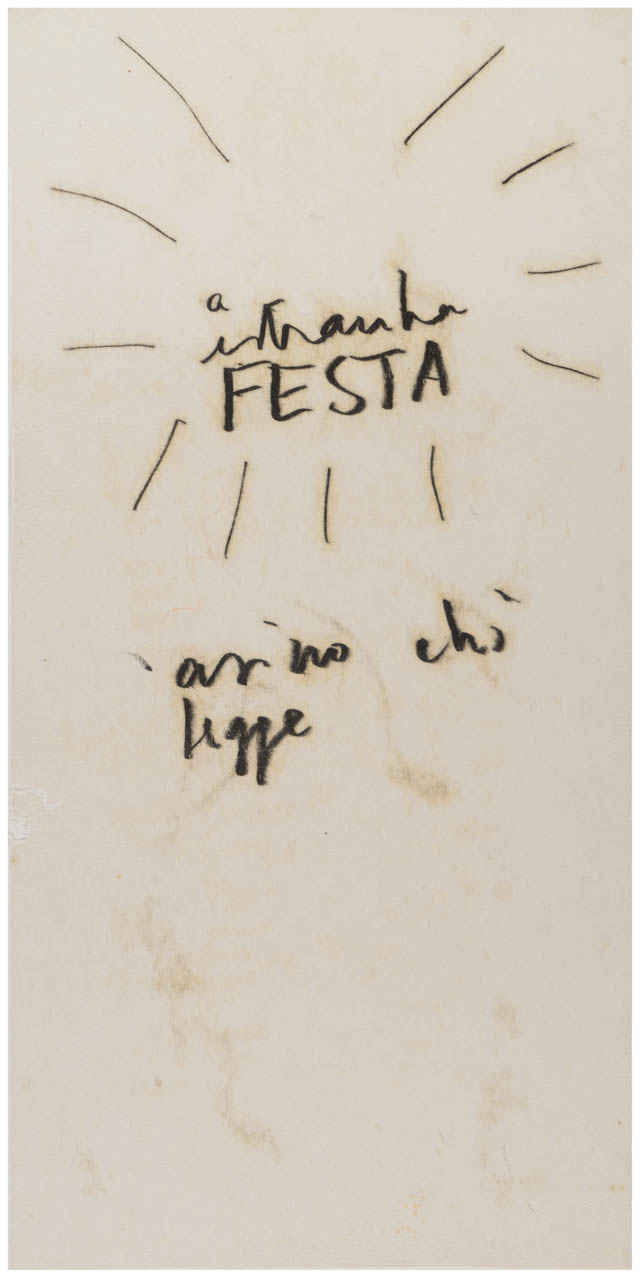

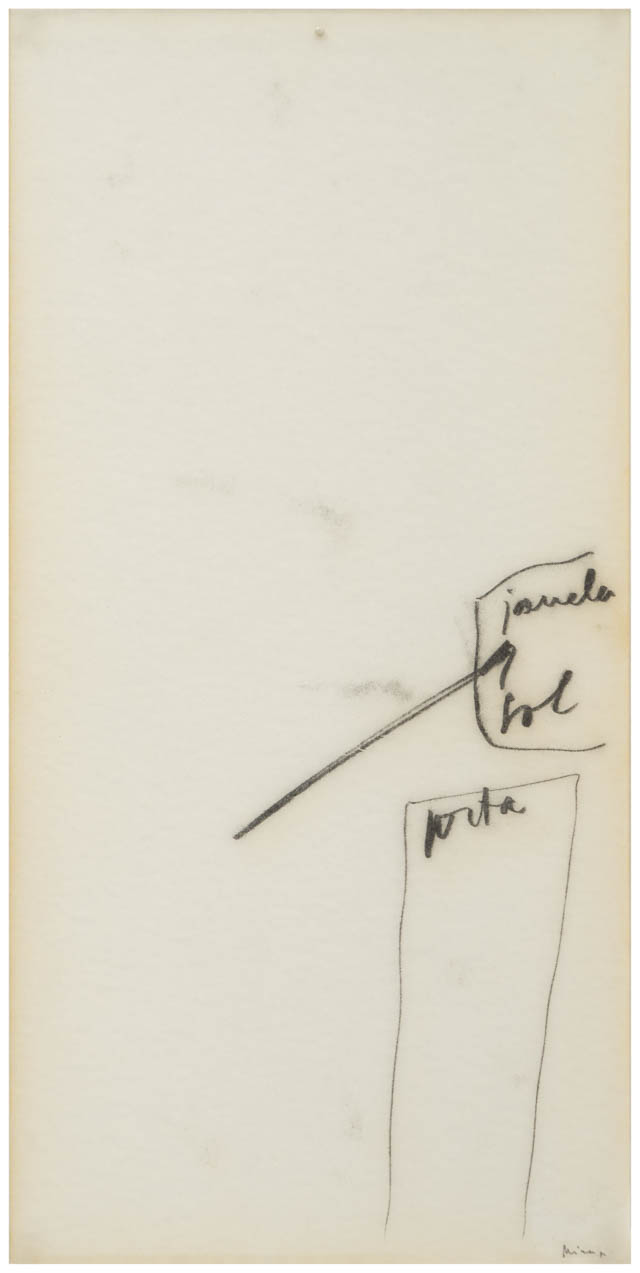

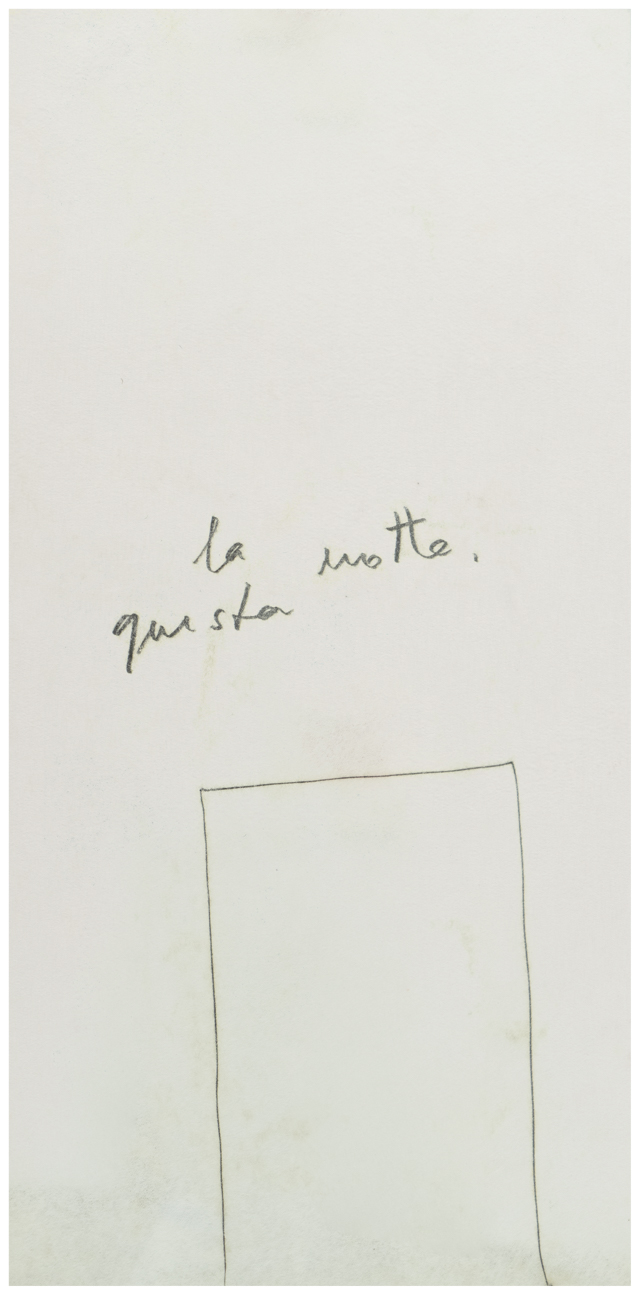

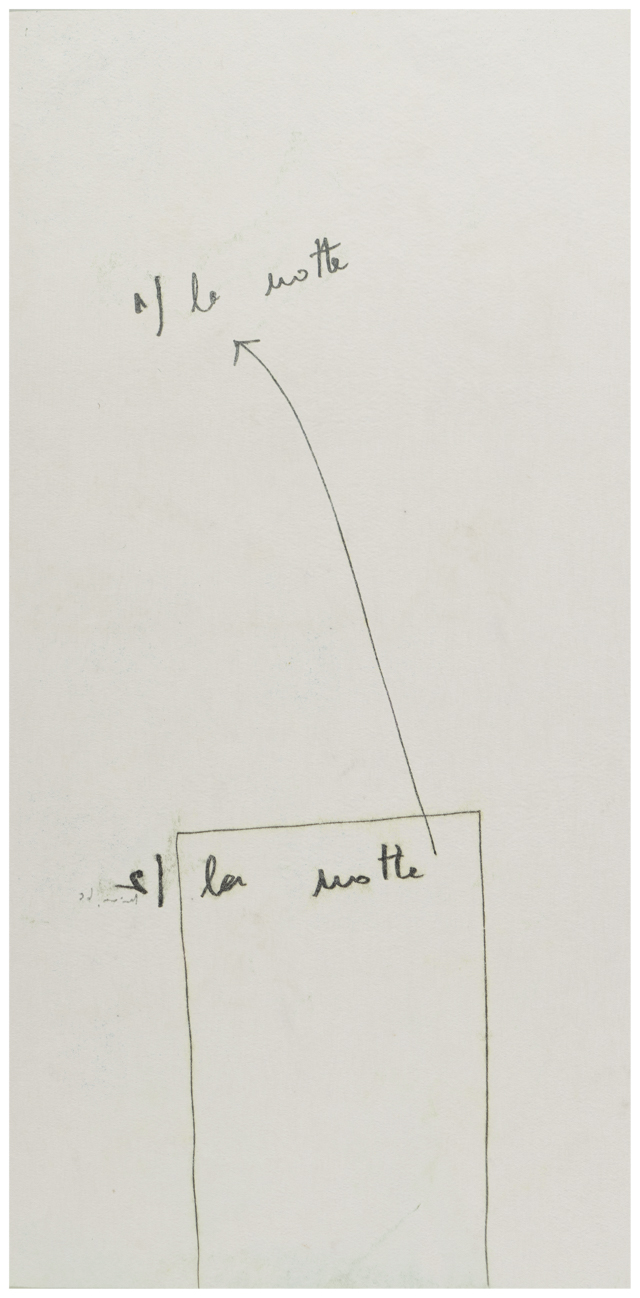

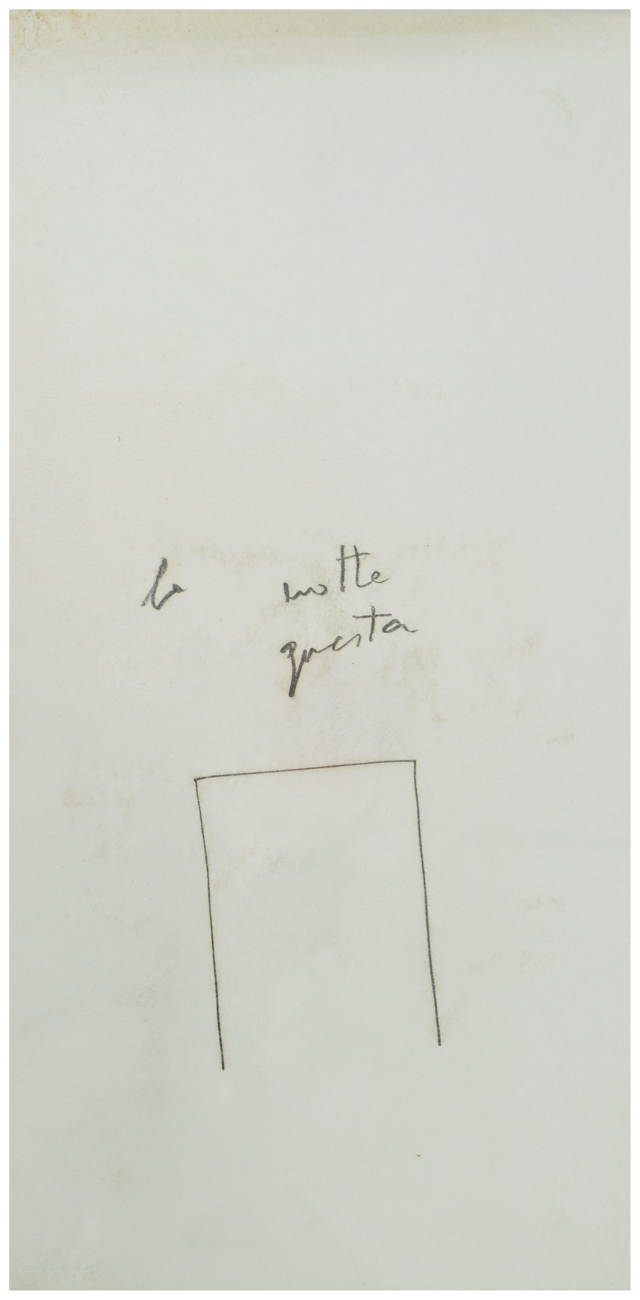

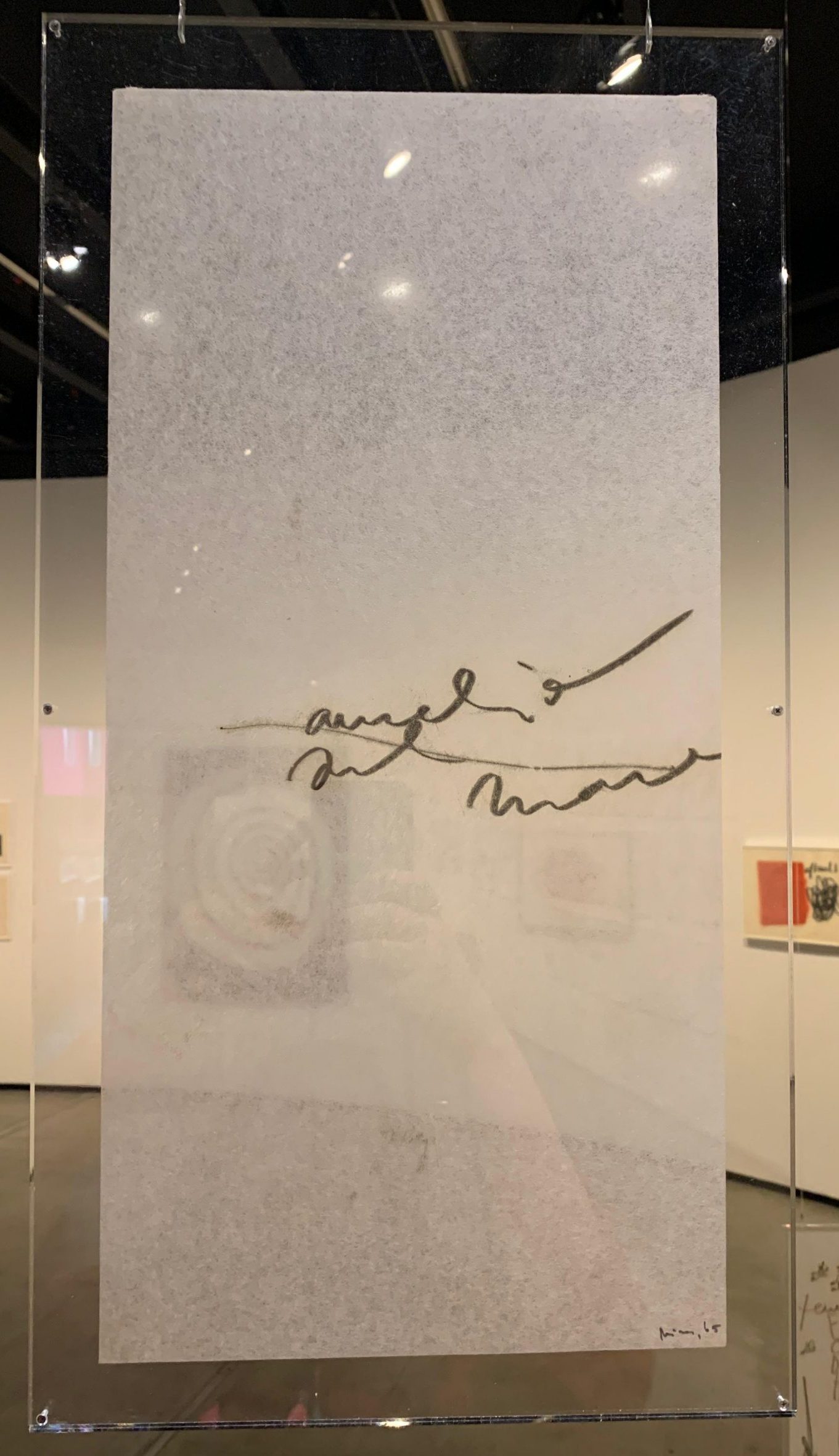

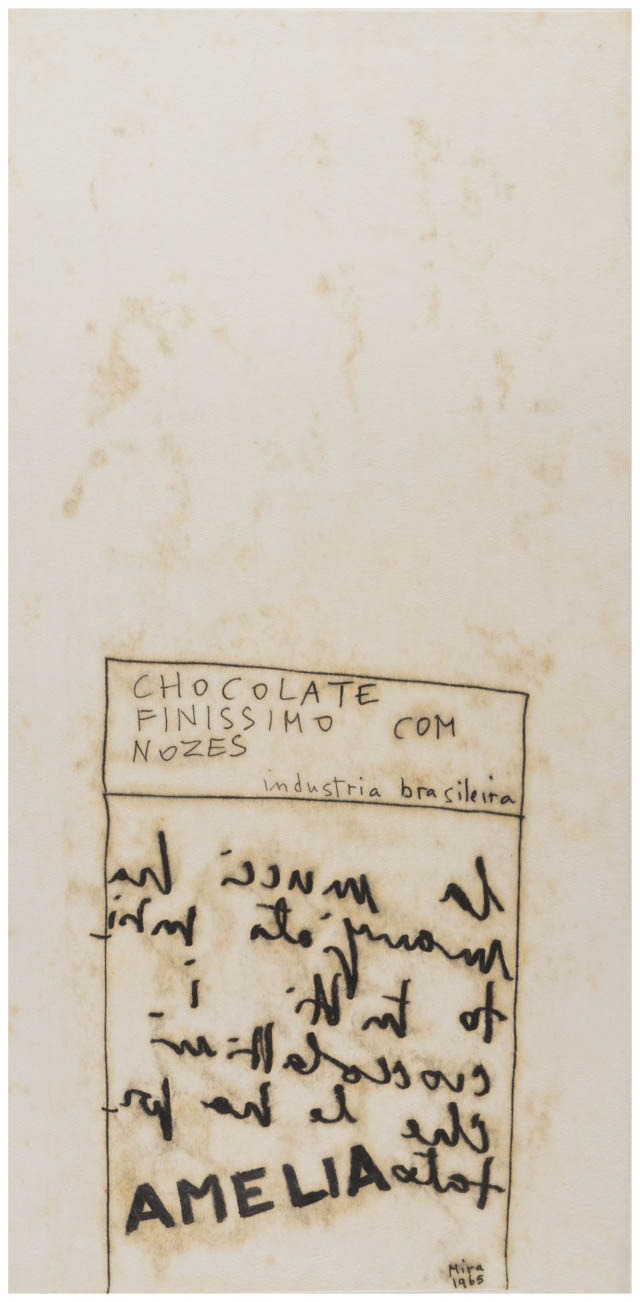

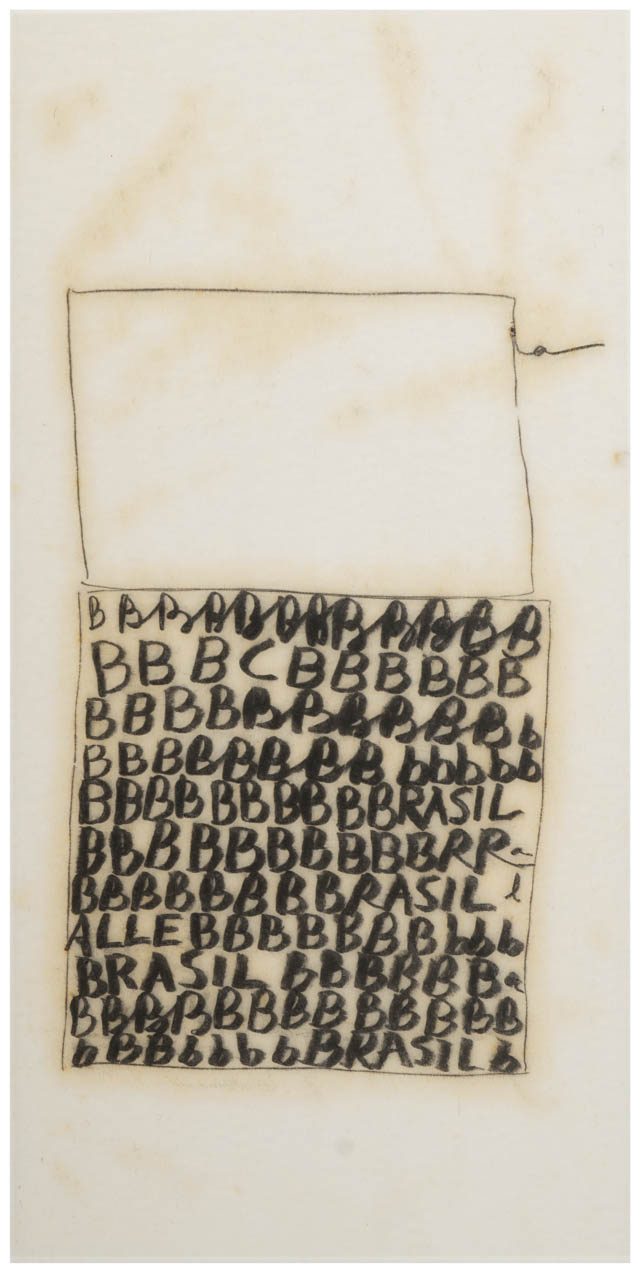

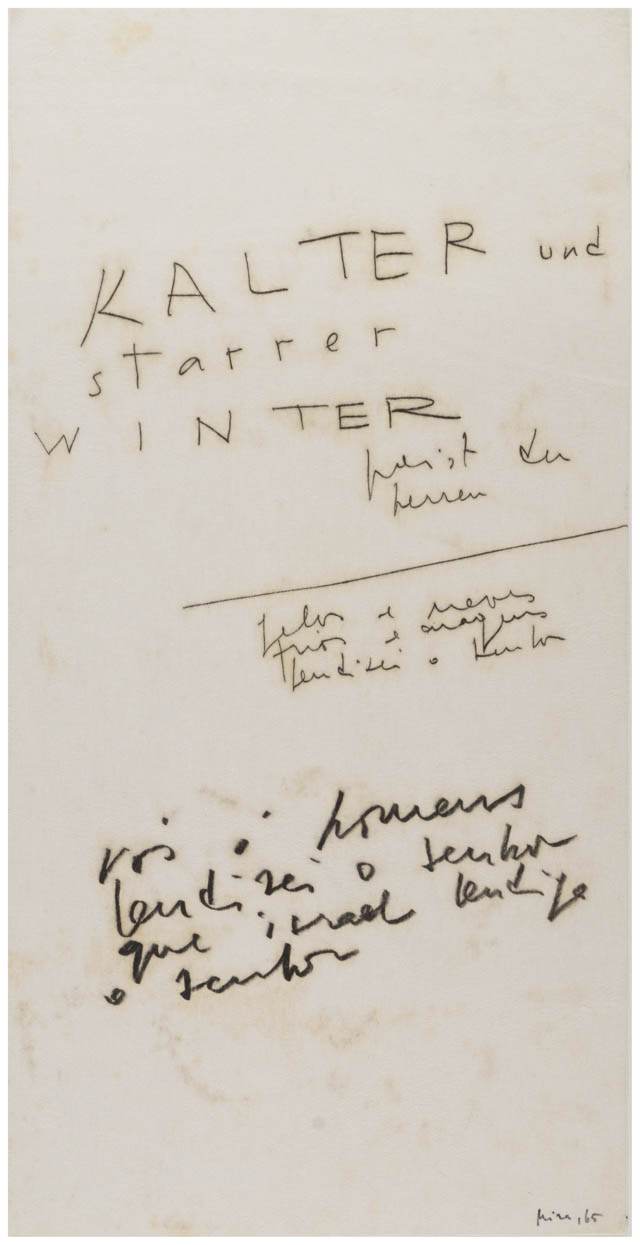

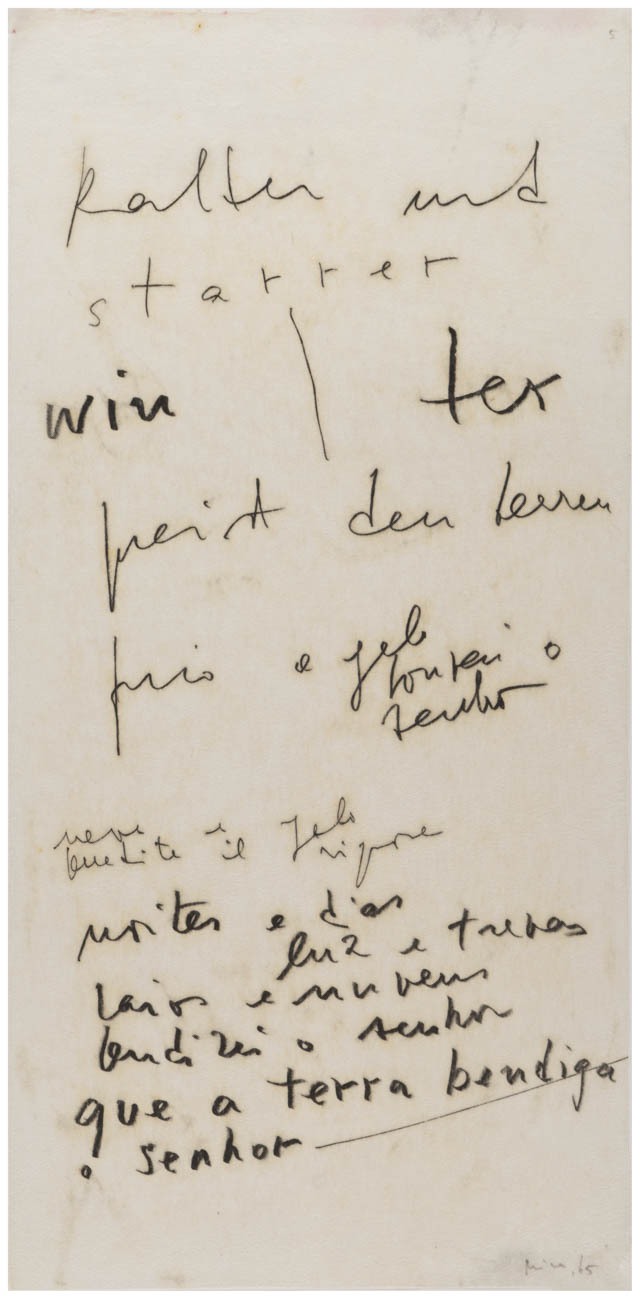

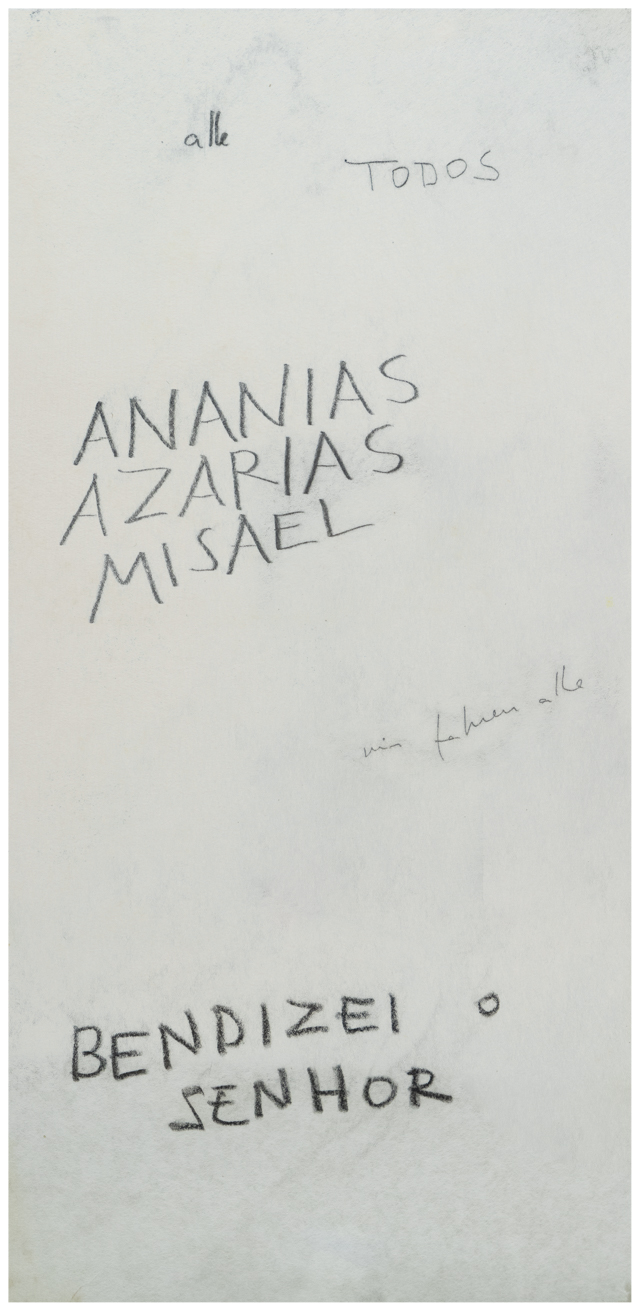

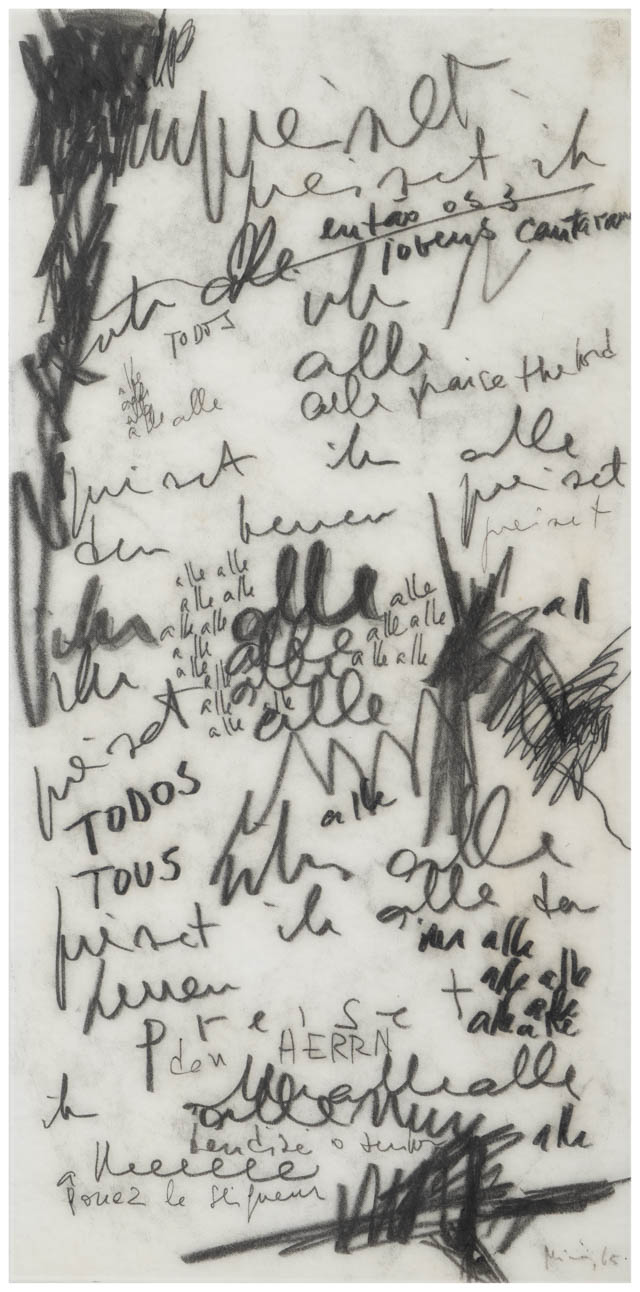

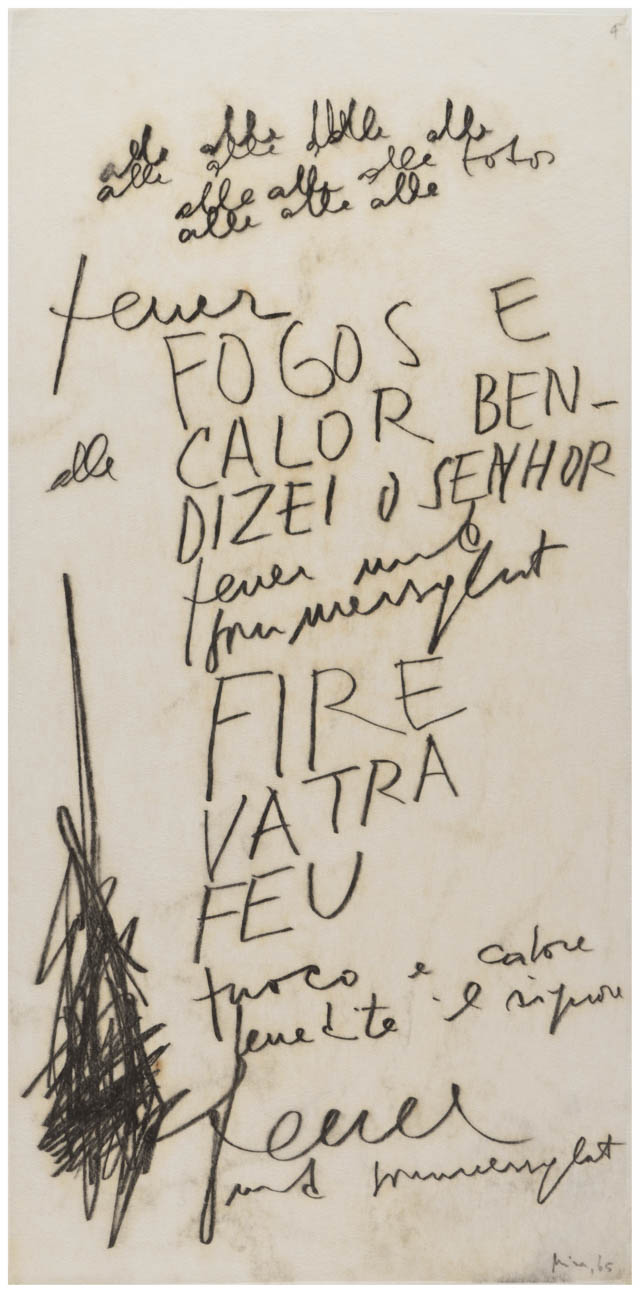

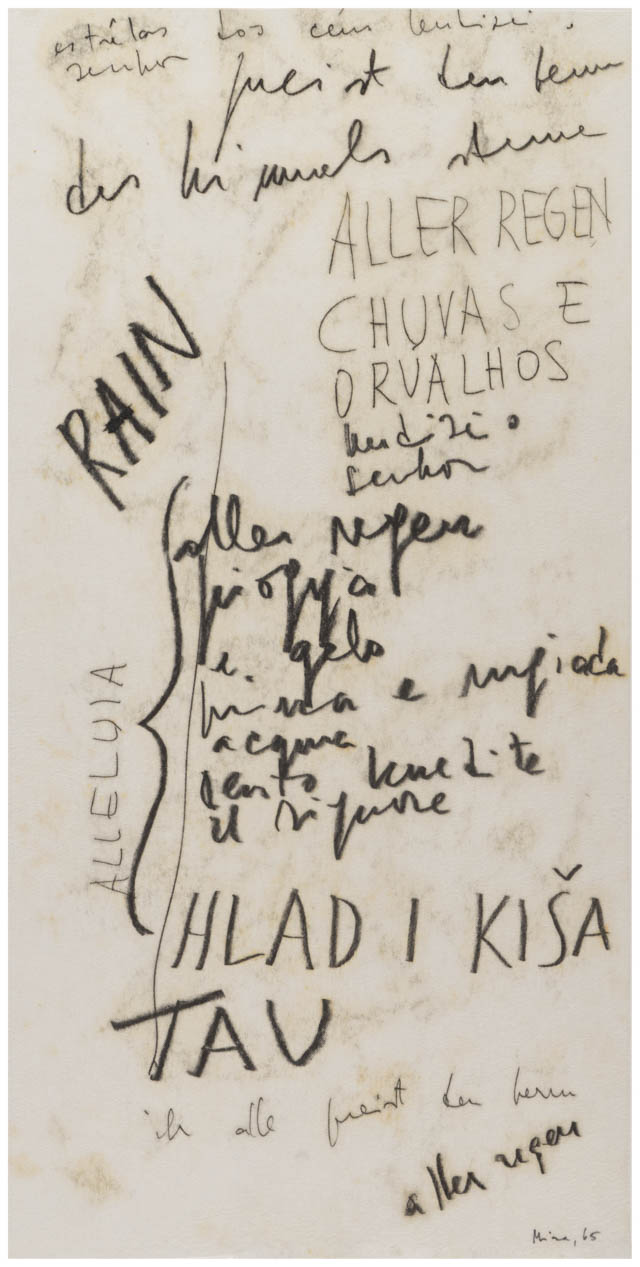

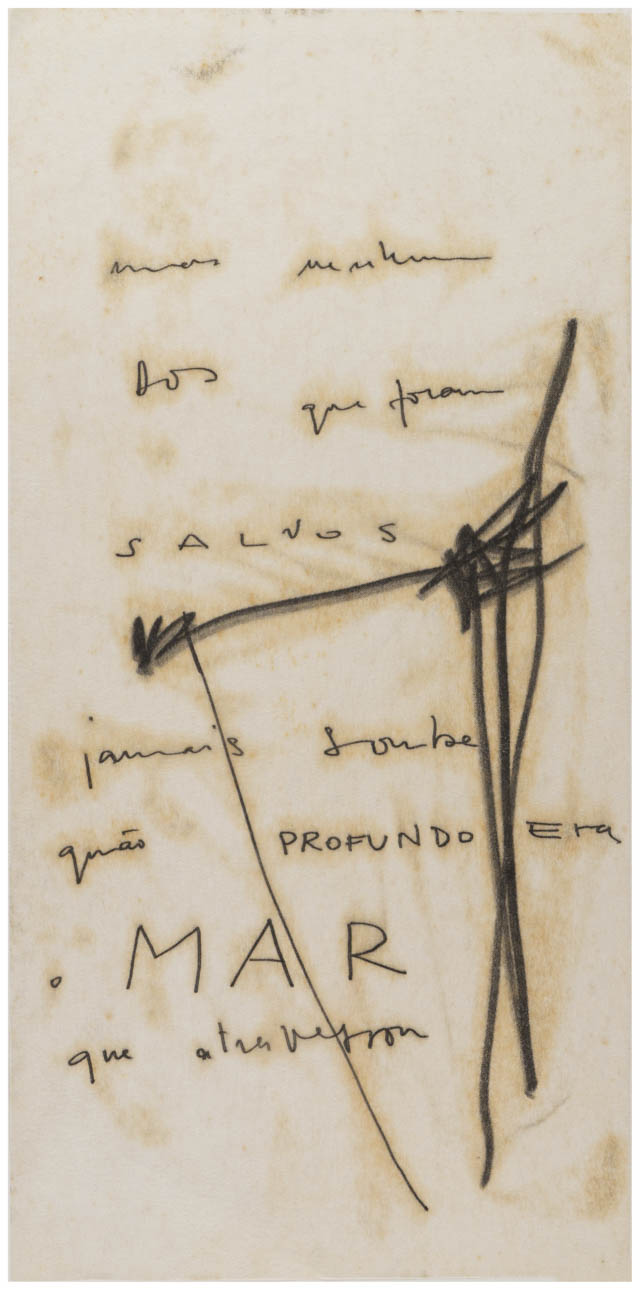

Certa vez, Mira ganhou um imenso volume de papel japonês – frágil, transparente, difícil de manusear. A natureza do papel a levou por muitas experiências, até que se deparou com a monotipia. Em dois anos, calcula-se que Mira produziu mais de duas mil monotipias com tinta preta à óleo em papel de arroz. Após entintar uma superfície lisa e polvilhar talco sobre ela para diminuir a transferência involuntária de tinta, pousava sobre ela a folha de papel retangular e desenhava em seu dorso com as unhas ou outro instrumento pontiagudo. A pressão do traço mais ou menos fino, mais ou menos regular, fazia a tinta impregnar as fibras orgânicas do papel translúcido, formando riscos e manchas visíveis, na frente e no verso do papel. Cada resultado dessa sequência de gestos era único, irrepetível, ainda que ela com frequência produzisse grandes grupos de obras com variações de elementos recorrentes. A solução para apresentar essas obras entre placas de acrílico suspensas possibilitou à artista enfatizar as múltiplas possibilidades de observação e leitura de suas obras translúcidas, experimentando a constituição de distâncias, direções de leitura e relações entre obra e público. Esse recurso desdobrou-se na criação dos objetos gráficos de Mira, em que ela reunia múltiplas monotipias ou datiloscritos entre duas amplas placas de acrílico, produzindo uma espécie de aglomeração de páginas, desenhos e grafias percebidos em contiguidade.

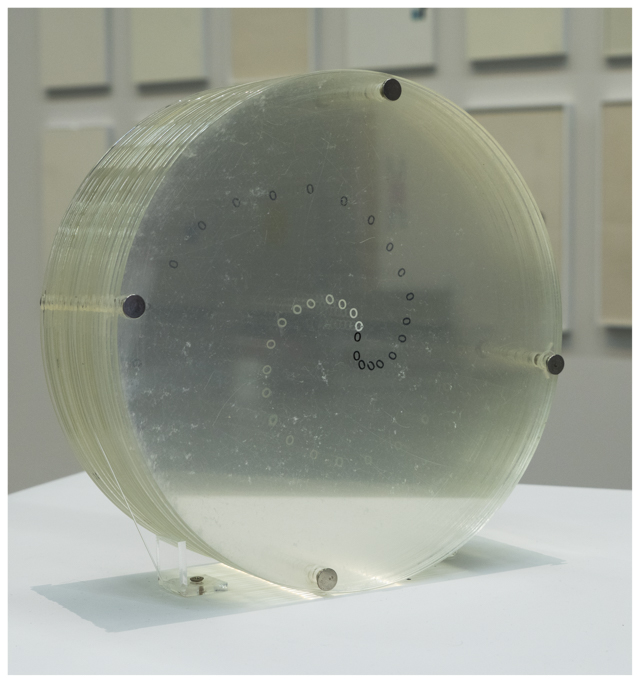

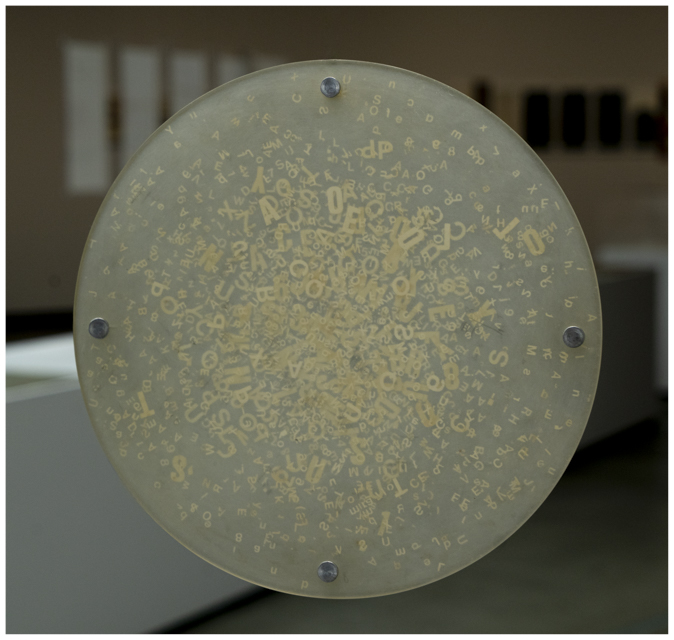

At one point, Mira received an immense volume of Japanese paper – fragile, transparent, difficult to handle. The nature of the paper led her through many experiments, until she encountered monotype. Over two years, it is estimated that Mira produced more than two thousand monotypes using black oil ink on rice paper. After inking a smooth surface and dusting it with talcum powder to reduce the unintentional transfer of ink, she would place a rectangular sheet of paper on top and draw on its back with her fingernails or another sharp instrument. The pressure of the line, more or less fine, more or less regular, caused the ink to impregnate the organic fibers of the translucent paper, forming visible lines and stains on both the front and back. Each result of this sequence of gestures was unique, unrepeatable, even though she often produced large groups of works with variations on recurring elements. The solution to present these works between suspended acrylic sheets allowed the artist to emphasize the multiple possibilities of viewing and interpreting her translucent works, experimenting with the creation of distances, reading directions, and relationships between the artwork and the public. This approach evolved into Mira’s graphic objects, where she combined multiple monotypes or typed texts between two large acrylic plates, producing a kind of aggregation of pages, drawings, and writings perceived in close proximity.

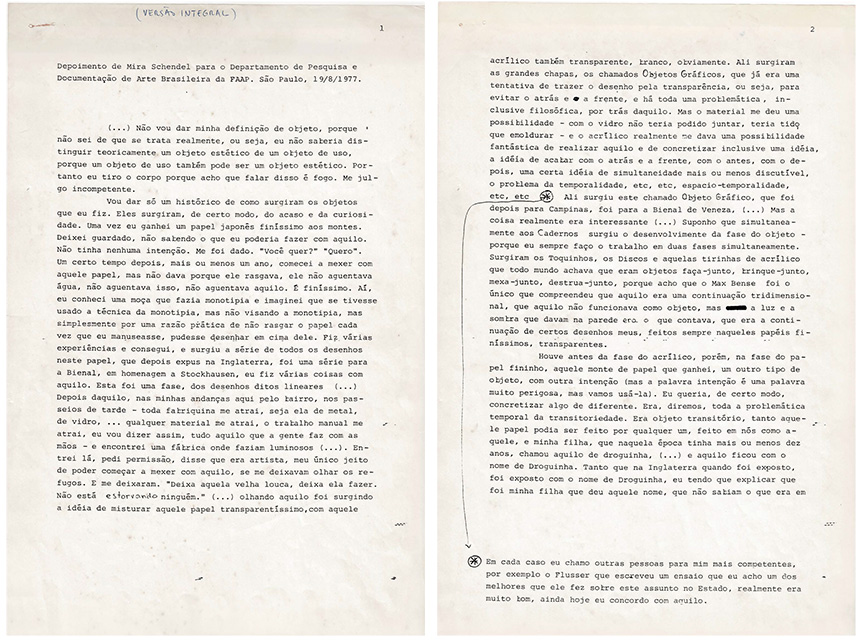

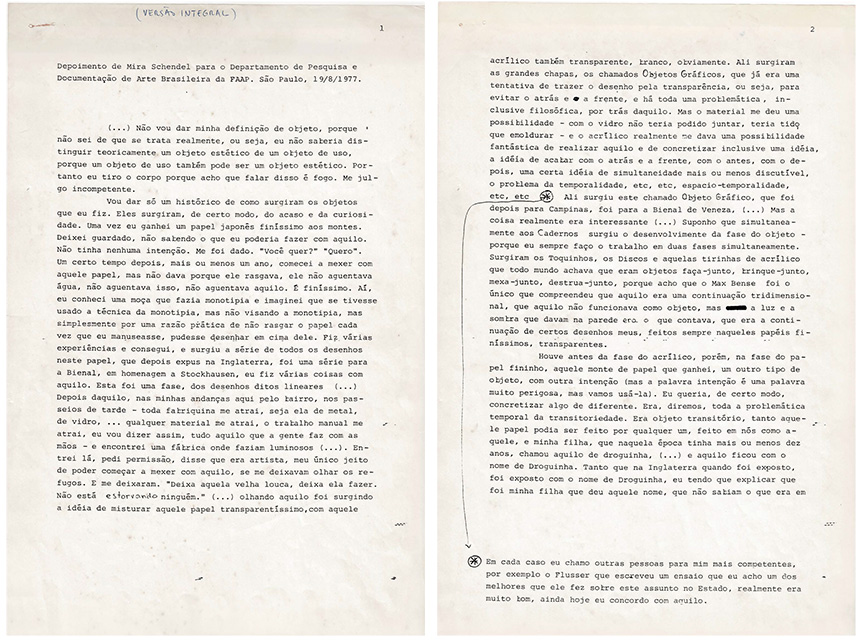

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP"

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP"

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP

Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP. São Paulo, 1/9/8/1977.

(…) Não vou dar minha definição de objeto, porque não sei de que se trata realmente, ou seja, eu não saberia distinguir teoricamente um objeto estético de um objeto de uso, porque um objeto de uso também pode ser um objeto estético. Portanto eu tiro o corpo porque acho que falar disso é fogo. Me julgo incompetente.

Vou dar só um histórico de como surgiram os objetos que eu fiz. Eles surgiram, de certo modo, do acaso e da curiosidade. Uma vez eu ganhei um papel japonês finíssimo aos montes. Deixei guardado, não sabendo o que eu poderia fazer com aquilo. Não tinha nenhuma intenção. Me foi dado. “Você quer?” “Quero.” Um certo tempo depois, mais ou menos um ano, comecei a mexer com aquele papel, mas não dava porque ele rasgava, ele não aguentava água, não aguentava isso, não aguentava aquilo. É finíssimo. Aí, eu conheci uma moça que fazia monotipia e imaginei que se tivesse usado a técnica da monotipia, mas não visando a monotipia, mas simplesmente por uma razão prática de não rasgar o papel e cada vez que eu manuseasse, pudesse desenhar em cima dele. Fiz várias experiências e consegui, e surgiu a série de todos os desenhos neste papel, que depois expus na Inglaterra, foi uma série para a Bienal, em homenagem a Stockhausen, eu fiz várias coisas com aquilo. Esta foi uma fase, dos desenhos ditos lineares (…)

Depois daquilo, nas minhas andanças aqui pelo bairro, nos passeios de tarde – toda fabriquina me atrai, seja ela de metal, de vidro, … qualquer material me atrai, o trabalho manual me atrai, eu vou dizer assim, tudo aquilo que a gente faz com as mãos – e encontrei uma fábrica onde faziam luminosos (…). Entrei lá, pedi permissão, disse que era artista, meu único jeito de poder começar a mexer com aquilo, se me deixavam olhar os refugos. E me deixaram. “Deixa aquela velha louca, deixa ela fazer. Não está estorvando ninguém.” (…) olhando aquilo foi surgindo a idéia de misturar aquele papel transparentíssimo, com aquele acrílico também transparente, branco, obviamente. Ali surgiram as grandes chapas, os chamados Objetos Gráficos, que já era uma tentativa de trazer o desenho pela transparência, ou seja, para evitar o atrás e a frente, e há toda uma problemática, inclusive filosófica, por trás daquilo. Mas o material me deu uma possibilidade – com o vidro não teria podido juntar, teria tido que emoldurar – e o acrílico realmente me dava uma possibilidade fantástica de realizar aquilo e de concretizar inclusive uma idéia, a idéia de acatar com o atrás e a frente, com o antes, com o depois, uma certa idéia de simultaneidade mais ou menos discutível, o problema da temporalidade, etc, etc, espaço-temporalidade, etc, etc* Ali surgiu este chamado Objeto Gráfico, foi depois para Campinas, foi para a Bienal de Veneza, (…) Mas a coisa realmente era interessante (…) Suponho que simultaneamente aos Cadernos surgiu o desenvolvimento da fase do objeto – porque eu sempre faço o trabalho em duas fases simultaneamente. Surgiram os Toquinhos, os Discos e aquelas tirinhas de acrílico que todo mundo achava que eram objetos faça-junto, brinque-junto, mexa-junto, destrua-junto, porque acho que o Max Bense foi o único que compreendeu que aquilo era uma continuação tridimensional, que aquilo não funcionava como objeto, mas a luz e a sombra que davam na parede era o que contava, que era continuação de certos desenhos meus, feitos sempre naqueles papéis finíssimos, transparentes.

Houve antes da fase do acrílico, porém, na fase do papel fininho, aquele monte de papel que ganhei, um outro tipo de objeto, com outra intenção (mas a palavra intenção é uma palavra muito perigosa, mas vamos usá-la). Eu queria, de certo modo, concretizar algo de diferente. Era, diremos, toda a problemática temporal da transitoriedade. Era o objeto transitório, então o papel podia ser feito por qualquer um, feito em nós como aquele, e minha filha, que naquela época tinha mais ou menos dez anos, chamou aquilo de droguinha, (…) e aquilo ficou com o nome de Droguinha. Tanto que na Inglaterra quando foi exposto, foi exposto com o nome de Droguinha, eu tendo que explicar que foi minha filha que deu aquele nome, que não saíam o que era em português (…)

*Em cada caso eu chamo outras pessoas para mim mais competentes, por exemplo o Flusser que escreveu um ensaio que eu acho um dos melhores que ele fez sobre este assunto no Estado, realmente era muito tom, ainda hoje eu concordo com aquilo.

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP

Mira Schendel, "Depoimento de Mira Schendel para o Departamento de Pesquisa e Documentação de Arte Brasileira da FAAP

Mira Schendel’s testimony to the Department of Research and Documentation of Brazilian Art at FAAP. São Paulo, August 19, 1977.

(…) I won’t share my definition of an object because I don’t really know what it’s about. I wouldn’t be able to theoretically distinguish an aesthetic object from an object of use, because an object of use can also be an aesthetic object. So I’ll step back, as I think talking about it is tricky. I consider myself unqualified.

I’ll just share a brief history of how the objects I made came about. They arose, in a way, from chance and curiosity. Once, I received heaps of the finest Japanese paper. I stored it away, not knowing what I could do with it. I had no intentions. It was given to me. “Do you want it?” “Yes, I do.” A while later, maybe a year, I started experimenting with the paper, but it would tear; it couldn’t handle water, it couldn’t handle this or that. It was extremely thin. Then, I met a woman who did monotype printing, and I thought of using the monotype technique – not aiming at monotypes, but simply for practical reasons, so the paper wouldn’t tear and I could draw on it as I handled it. I tried several things, succeeded, and that led to a series of drawings on this paper, which I later exhibited in England. I also made a series for the Biennial, in homage to Stockhausen. I created several things with it. That was one phase – the so-called linear drawings (…)

After that, during my walks around the neighborhood in the afternoons – every small factory attracts me, whether it’s metal, glass… any material draws me in. I’m fascinated by manual work. I’ll put it this way: everything we make with our hands interests me. I came across a factory where they made illuminated signs (…). I went in, asked for permission, said I was an artist – this was the only way I could begin working with the material – if they would let me look at the scraps. And they did. “Let that crazy old lady be. Let her do her thing. She’s not bothering anyone.” (…) While looking around, the idea came to mix that ultra-thin paper with the transparent acrylic, also white, of course. And that’s where the large sheets came from, the so-called Objetos Gráficos [Graphic Objects], which was an attempt to include drawing through transparency, to avoid the front and back. There’s a whole problem behind it, including a philosophical one. But the material gave me a possibility – with glass, I wouldn’t have been able to combine them; I would have had to frame them – and acrylic really offered me a fantastic way to realize it and even materialize an idea: the idea of dealing with front and back, before and after, a certain idea of simultaneity, somewhat debatable. It touched on the problem of temporality etc., etc., space-time, etc., etc.* This is how the so-called Objeto Gráfico emerged. It later went to Campinas, to the Venice Biennale, (…) But the thing was really interesting. (…) I assume that, at the same time as the Cadernos [Notebooks], the object phase developed – because I always work on two phases simultaneously. That’s when the Toquinhos [Little things], the Discos [Disks], and those strips of acrylic appeared, and everyone thought they were objects to make together, play together, mess with together, destroy together. I think Max Bense was the only one who understood that that was a three-dimensional continuation, that they didn’t function as objects but rather as shadows and light on the wall, and that is what mattered. It was a continuation of some of my drawings, always made on those thin, transparent papers.

However, before the acrylic phase, during the phase with the thin paper, that huge amount of paper I received, there was another type of object with a different intention (“intention” is a very dangerous word, but we’ll use it). I wanted, in a way, to materialize something different. It was, let’s say, the whole temporal issue of transience. It was the transient object, so the paper could be made by anyone, made with knots just like that one. And my daughter, who at that time was about ten years old, called it Droguinha [Little Nothing] (…), and that name stuck. So much so that when it was exhibited in England, it was shown under the name Droguinha, and I had to explain that it was my daughter who came up with that name, as they couldn’t figure out what it was in Portuguese (…)

*In each case, I call upon others who are more competent than I am, such as Flusser, who wrote an essay that I consider one of his best on this subject for the Estado newspaper. It was truly very good, and I still agree with it to this day.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, c. 1960-1966

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, c.1964-1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1964

Sem título, c. 1964-1966

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1966

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1964

Sem título, 1964

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título [Toquinhos] , 1972

Sem título [Toquinhos] , 1972

Sem título [Toquinhos] , 1972

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1966

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, c. 1960-1966

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título [Objeto Gráfico], 1967-1968

Sem título [Objeto Gráfico], 1967

Sem título, 1971

Sem título, da série Toquinhos, c. 1970

Sem título, 1972

Sem título [Objeto Gráfico], 1967

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, 1964

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, s.d.

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, 1965

Sem título, c. 1964-1965